originally published in

Video and the Arts Magazine, Winter 1986

Larry Cuba is one of the most important artists currently working in the tradition known variously as abstract, absolute or concrete animation. This is the approach to cinema (film and video) as a purely visual experience, an art form related more to painting and music than to drama or photography. Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, Norman McLaren and the Whitney brothers are among the diverse group of painters, sculptors, architects, filmmakers and video and computer artists who have made distinguished contributions to this field over the last 73 years.

Insofar as it is understood as the visual equivalent of musical composition, abstract animation necessarily has an underlying mathematical structure; and since the computer is the supreme instrument of mathematical description, it's not surprising that computer artists have inherited the responsibility of advancing this tradition into new territory. Ironically, very few artists in the world today employ the digital computer exclusively to explore the possibilities of abstract animation as music's visual counterpart. John Whitney, Sr. is the most famous, and rightly so: he was the first to carry the tradition into the digital domain, and his book Digital Harmony is among the most rigorous (if also controversial) theoretical treatments of the subject. But for me Cuba's work is by far the more aesthetically satisfying. Indeed, if there is a Bach of abstract animation it is Larry Cuba.

Words like elegant, graceful, exhilarating or spectacular do not begin to articulate the evocative power of these sublime works characterized by cascading designs, startling shifts of perspective and the ineffable beauty of precise, mathematical structure. They are as close to music --particularly the mathematically transcendent music of Bach-- as the moving-image arts will ever get.

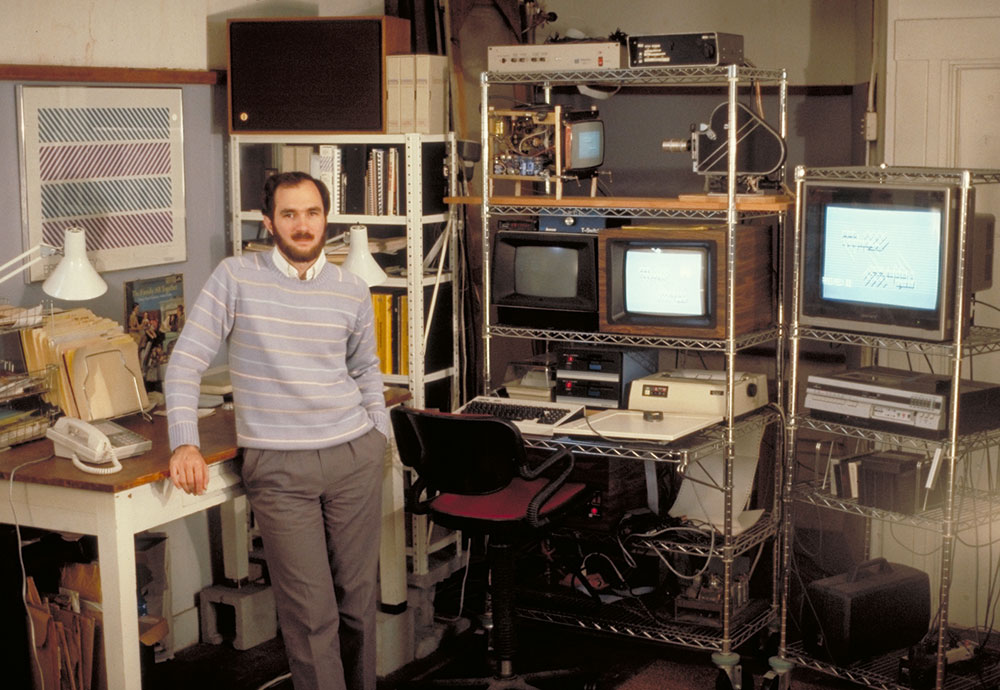

Cuba has produced only four films in thirteen years. The best known are 3/78 (Objects and Transformations) (1978) and Two Space (1979). The imagery in both consists of white dots against a black field. In 3/78 sixteen "objects," each consisting of a hundred points of light, perform a series of precisely choreographed rhythmic transformations against a haunting, minimal soundtrack of the shakuhachi, the Japanese bamboo flute. Cuba described it as “an exercise in the visual perception of motion and musical structure." In Two Space, patterns resembling the tiles of Islamic temples are generated by performing a set of symmetry operations (translations, rotations, reflections, etc.) upon a basic figure or "tile." Twelve such patterns constructed from nine different animating figures are choreographed to produce illusions of figure-ground reversal and afterimages of color. This is set against 200 year old Javanese gamelan music. Both films have won numerous awards and have been exhibited at festivals around the world . Calculated Movements, Cuba's first work in six years, premiered in July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and was also included in the film and video show of SIGGRAPH '85, the international computer graphics conference. It is a magnificent work, destined to join 3/78 and Two Space as a classic of abstract animation. It represents a formal departure from its predecessors. Whereas they were produced on expensive vector graphic equipment at institutional facilities, using a mainframe and minicomputer respectively, Calculated Movements was produced at Cuba's studio in Santa Cruz on the Datamax UV-1 personal computer with Tom DeFanti's Zgrass graphics language. This is a raster-graphic system that allowed Cuba to work for the first time with solid areas and "volumes" rather than just dots of light. The result, both in design and dynamism, is strongly reminiscent of the films of Oskar Fischinger.

Computer animation is neither film nor video --those are simply media through which a computer's output can be stored, distributed and displayed. Previously Cuba released his work only on film, but Calculated Movements is available on both film and video. We talked about the theory and practice of abstract animation, about the computer as an instrument of that practice, and about the production of Calculated Movements.

GENE: There's a widespread belief that mathematics and intuition are somehow antithetical; yet the outstanding characteristic of your work is a graceful musicality that feels profoundly intuitive, even spiritual.

LARRY: I appreciate your saying that because that's clearly my goal. Music does do that, and it has an underlying mathematical structure, although I think no one's really clear on how or why it affects us the way it does, what the rules are. A lot of people are working on that and have theories about it. It seems my job is to see how we can do it graphically.

What I'm trying to do is, I think, very difficult. The creative process here appears to be so much different than from most art forms --using mathematics to create pictures, trying to make them affect us the way music does. ' How do I create these things? ... " I think it comes from paying attention to things that affect me. When I see visuals that elicit that response I think about why, where it came from, what is the quality? In a sense, this is what abstraction is about: what's the essence without the details? I'm always searching for that. In computer graphics today there's, this great push toward simulating reality, especially natural phenomena. Realistic simulations of plants, for example. Plants are beautiful, so naturally the simulations are beautiful. Plants, mountains, trees, the pattern water makes when it goes over a rock-these are evocative in the same way music is. But I want to know why. I don't want to simply reproduce the pattern; I want to know what it is about the pattern that evokes that feeling. And what's the relation between that pattern and its mathematical description?

What they're finding now as they attempt to simulate things like trees is that there's a balance between total randomness and an order that's very predictable. Leaves of a tree are different in some ways and the same in others. So there's a delicate balance between the order which makes them the same and the randomness which makes them different. It's what makes the tree so aesthetically satisfying. And that's where the underlying mathematics comes in. In my work, I start with a very ordered system and continually add the variations which make it more and more interesting.

GENE: When you show your films in person, you frequently talk about the history of hand-drawn abstract animation and show examples of work by Fischinger and McLaren and others.

LARRY: That's to establish an appropriate context for the work. Because typically the interest in these films comes from an interest in the technology, the fact that it's computer graphics or computer animation. It seems the major assumed goal is to push the state of the art technologically. I'm not interested in that. My work is not part of that big race for the flashiest, zoomiest, most chrome, most glass, most super-rendered image. My interest is experimental animation as the design of form in motion, independent of any particular technology used to create it. The underlying problems of design in motion are universal to everyone working in this tradition whether they use the computer or not. So in that sense what I do is not "computer art.”

On the other hand the technology is clearly important. If you think about the process used in abstract animation it does become important that you’re using a computer in the way it affects your vocabulary. Because if you start with these mathematical structures you can discover imagery that you have not previsualized but have ‘found’ within the dimensions of the search space. Certainly every artist is engaged in some form of dialogue with their tools and their medium, whether it's brushes on paint and paper or a video synthesizer or a computer. But my tool is the mathematics and the programming that depend on a computer as the medium to execute it. So in that sense the computer adds a new dimension to this field of exploration which started with Gina and Corra, the Italian Futurists who are attributed with the earliest abstract films in 1912. They were talking 20th century dynamism. Today we're talking mathematics.

GENE: Do you have a formal background in math?

LARRY: I don’t use any math more advanced than what you learn in high school. Just algebra. But I do have an interest in mathematics as a domain of thought. It’s a lot like art --a world in itself, apart from everyday reality yet also underlying everyday reality. And the more advanced the mathematics the more abstract it is. It becomes more a world of its own. You can say the same about art as it be comes more abstract.

GENE: How do you work? Do you think up an image and then work backward from image to an equation?

LARRY: A little of both. It's ironic, but I find that when I visualize a specific image and program it up, it never looks as interesting as I thought it would. But that's the beginning. I can see what's wrong with it and that's where I start making changes. It's a real exploration through a space of imagery that I'm led to through this dialog,so that every experiment leads to the next experiment.

GENE: That's the whole point of experimental work. It's research.

LARRY: Or art. Someone once asked what I mean by the term "experimental film." What makes them experimental? I said because they’re not previsualized. They're the result of experiments and dialog with the medium. And he said, 'Well, all art is like that, that's what art is." I said all art is like that but all film is not. We're much more used to films being preconceived, both in content and execution. Even many people with whom I share the same intent will listen to a piece of music, come up with images, storyboard them and animate them. So that by the time they get to the production stage the result is almost a foregone conclusion.

That's much less of a dialog than my approach and in that sense it's not as experimental. Also there's the danger that the music is carrying the piece: take away the sound and there's not much left. In my work, the visuals come first. I'm trying to discover what works visually, so I never start with music. That would be starting with a composition that already exists, and composition is the problem. I don't have an image of the final film or even any of the scenes before I start programming. I only have basic structural ideas that come from algebra, or from the nature of the [computer] drawing process, or from the hierarchical structure of the items in the scene and how they will dance --the choreographic movements from a mathematical point of view.

GENE: Calculated Movements differs from your earlier films more than they differ from one another.

LARRY: The most obvious difference comes directly from the hardware. The other films were done on vector systems, so I was using dots. Going to the Zgrass machine meant not only going down from a mainframe to a mini to a micro but also going from vector to raster graphics. So this is my new palette, so to speak. New in two ways: I could draw solid areas so that my form became delineated areas instead of just dots, and I had four colors: white, black, light grey and dark gray. Every film I've made was done on a different system. This is the only piece I've made on this machine. So the evolution of my work is directly parallel to the evolution of systems I've used.

Two Space was not composed in real time. It was done in the traditional manner of writing the program, running it on a computer in animation mode where it takes several seconds per frame, then it goes to film, then the film is processed, and only then can you see it move. As a result, the rhythmic structure of Two Space is rather limited. There isn't much variation. The pacing is very much like the gamelan music I used on the soundtrack, regular and continuous. The advantage was that working in animated time imposed no limit on the complexity of the image. As long as I was willing to wait it would continue to draw dots. So the images could be dense and they could be of any arbitrary formulation --the computation required to calculate where the dot goes could be arbitrarily complex. For 3/78, I used a real time system. When I ran my programs I could see the animation immediately. That feedback allowed me to deal with a more varied rhythmic structure. There's much more variation in 3/78, so it feels more musical in the western sense of polyrhythmic structure. But there was a trade-off because there's a limit to what can be calculated and drawn in real time, and that imposed a limitation on its visual complexity. With Calculated Movements, I was back working in animated time. Consequently, I don't think it's as rhythmic as 3/78 in the sense of a variety of movements. 3/78 is one continuous transformation from beginning to end whose movements start and stop and change speed according to a fairly complex score without much repetition, whereas each event in Calculated Movements has its own fixed internal rhythm. It comes and goes and there isn't much variation other than that. So in that sense it's more like Two Space.

GENE: It feels very fluid and elegant to me. Can you describe the compositional strategy?

LARRY: There are five movements that alternate between two types. The odd-numbered movements are each structured as a single event about a minute long in which ribbon-like figures follow a single trajectory against a middle gray background, and each scene represents a structural variation on this theme.

In the first movement a single rib bon appears, follows a trajectory and disappears; it's followed by another ribbon, then another, and so on, all following the same path. So there are no transformations in space but a large transformation in time---that is, the figures are shifted out of phase only in time but not two dimensionally. Another option is to spread them out in a two-dimensional pattern so they can be traversing this path simultaneously. So in the third movement they're shifted both in time and space. Also, because the figures are longer they overlap and form a dense array. They appear, go through the trajectory and disappear. In the fifth movement, they’re also shifted in time and space but they're shorter in length, so they look more like a flock of birds.

The strategy for the even-numbered movements, in contrast, was a collection of forty short events ranging from one and a half seconds to five seconds, orchestrated to appear and disappear at different intervals. Each event follows the same basic structure of a trajectory, repetition of the figure and some transformation spatially and temporally of each repetition. I designed these events using a random number generator that selected values for each parameter from within a predetermined range. Many events were generated this way, then I selected and orchestrated them intuitively. So the overall strategy for Calculated Movements is a two dimensional pattern whose parameters are: What is the path? How many figures are there? How far apart are they? What are the dimensions of each ribbon? And the phasing---how far apart in time are they? This is essentially an evolution of the Two Space approach. All of Two Space came from variations of the basic figure whose parameters were fixed for the whole film. The next step was to start varying those parameters to get more degrees of freedom. And that's Calculated Movements.

GENE: What about sound?

LARRY: Larry Simon and Craig Harris did the odd-numbered movements based on my suggestions. They used a computer-controlled Yamaha DX-7. These are the scenes that follow the same path and have the feel of being one long event, so they have one type of very melodic music almost Philip Glass style.

The other scenes were more difficult because their structure is more intricate- more isolated events. Rand Weatherwax did the sound for these using an Emulator Two, a digital sampling device like the Fairlight or the Synclavier that has a built-in sequencer. I found it would be easy to match the sequencing of sound events with graphics events by programming into the sequencer the same temporal structure as the images. So, because we synced up sonic events with graphic events you might say that the composition-in the sense of when notes appear and disappear-comes directly from the underlying structure that I had composed for the graphics. But when it came to what sounds to plug in for each event, Rand would pull out one of his library of effects and would modify it until I was satisfied. So in that sense it was a collaboration not unlike my collaboration with John Whitney as programmer for Arabesque. John didn't actually write the programs but he had very specific ideas. So who composed Arabesque? Well, it's John’s film creatively; I only worked as programmer, but I think if someone else had programmed it, it would have come out differently.

GENE: How long did you work on the visual composition?

LARRY: About two and a half years. The first few months are always spent developing tools in the particular language you're using. The language itself is a tool but then you create your own tools with it --called macros or sub routines-- to do generalized classes of things. That’s a reason why the generalized approach takes more time. For 3/78, I spent about three months developing the tools that would allow me to manipulate geometric figures and score them with different phasing and patterns and so on. Then came the matter of using that tool to score a specific sequence. So first I developed the tools and then I made the film.

But with Calculated Movements the tools evolved simultaneously with the visual composition. I started making serious progress only when I got a Lyon-Lamb video animation system about two years ago. Then I could do extended scenes on tape so I could see what I was doing. I'd program the scenes then run the computer for ten or twenty hours to produce the animation. I did have some preview during the still phase/ while I was developing the program. I could look at some images to make sure the program was running right. Then I’d run it and look at the tape, and that was the first time I actually saw the images move. At that point l’d frequently realize I needed a whole other set of tools so I'd rewrite the entire system and experiment some more. Over two years I generated about ninety minutes of working material, about a hundred individual shots. That represents an evolution of programs. So there was an evolution of the tool simultaneously with the evolution of the pictures-to the extent that I'd get way down the line and look back at the early pictures and realize I couldn't generate those pictures anymore because the software had evolved. I'd opened up new dimensions and closed off others. So it represents my own personal evolution. As Jane Veeder likes to say, the artist is the work in progress. This is two years of working on me. The films are like progress reports. They represent where I am at this point in the evolution.