Ferries For The San Francisco Bay Area; New Paradigms From

New Technologies

Chris Barry (Member), Bryan Duffty (Member), and Paul Kamen (Visitor)

Presented at the joint meeting of the Society of Naval Architects and

Marine Engineers, Asilomar, Pacific Grove, California

May 31 2002

Appendix A:

A Detailed Plan for a Berkeley to San Francisco Ferry Service

"Even

a journey of a thousand miles begins with a two-hour schlep to the

airport"

Chinese proverb

(slightly modified)

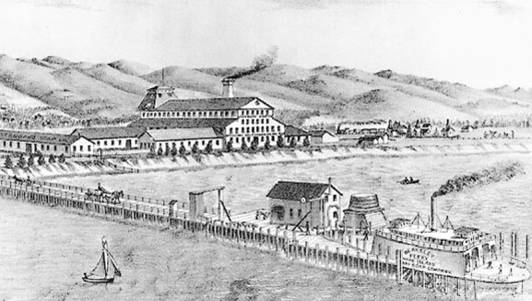

Figure A-1

Jacob's Landing in the late 19th

Century

Background

Ferry

service from Berkeley to San Francisco began in 1851 when James H. Jacobs built

the wharf at the mouth of Strawberry Creek, and ended in 1956 when the last

scheduled ferry left the end of the Berkeley Municipal Pier. The Bay Bridge

(1936), the proliferation of the private auto, and finally transbay BART

service (1973) all made ferries redundant and obsolete.

Temporary

ferry services have operated during a BART strike (1979) and during the closure

of the Bay Bridge following the Loma Prieta earthquake (1989).

But the

boats were old and slow, the docking arrangements inside the Berkeley Marina

were time consuming and the ridership could not be maintained.

Even in the

weeks following the Loma Prieta earthquake with the Bay Bridge closed, there

were never more than 500 morning commuters taking the ferry.

What the ferry can and cannot do

It is

recognized that a Berkeley ferry is not likely to significantly alleviate

vehicular congestion or improve regional air quality. It is primarily an

amenity and an alternative to other forms of private and public transportation.

However, because it will be possible to operate this ferry service without

significant public subsidy, funds will not be redirected from other modes of

public transportation. The probable lack of measurable impact on Bay Area

traffic congestion is therefore not a valid argument against the ferry service

proposed here.

What the

Berkeley ferry will do is increase mobility. Ferry service has become desirable

again because of the chronic congestion on the Bay Bridge and the saturation of

the BART system. For example, for those who do not live within walking distance

of a BART station, after about 8:00 am when the BART parking lots fill up there

are essentially no options but to drive to San Francisco. Crossing the bridge

by car on a weekday morning (or Saturday evening) is unpleasant and very slow,

and parking is expensive. The loss of the ability to move about the inner Bay

Area freely and comfortably has a high economic cost, and ultimately adds to

the pressure for suburban sprawl.

The Boat

Design evolution

begins with the selection of the number of passengers. See figure A-2, which

shows passengers per crew as a function of number of passengers. The first

local maximum, at 149 passengers, is chosen as the only economical point that

is consistent with modest ridership projections. Also, a significant increase

in first cost is incurred at larger capacities due to more rigorous construction

standards imposed by the Coast Guard for vessels carrying 150 passengers or

more.

Figure

A-2 Passengers per crew v. number of

passengers

The Coast

Guard allows a crew of two for a single deck design, but one additional crew is

required for each additional passenger deck. Therefore a single-deck design is

strongly indicated. There is also motivation for large deck area to accommodate

bicycles, dogs and possibly electric scooters.

Speed is

determined by the distance and the required transit time. 17 knots is

sufficient for a single boat to provide hourly service over the 5.6 mile route,

with 20 minute transit time and ten minute turn-around at the terminals. 18

knots is the specified service speed, to allow for adverse tides.

Figure A-3

shows the sensitivity of required speed to terminal turn-around time. This

implies multiple boarding points, whether docked bow-in or side-tied, to facilitate

very rapid loading and unloading.

Figure

A-3: Required speed and power v.

turnaround time

The ride

must be quiet and comfortable, with vessel motions comparable to larger vessels.

The seating arrangement should be spacious, allowing most passengers the choice

of a work table or a good view.

Fuel

efficiency must be extremely high and emissions must be extremely low.

To

summarize the primary requirements:

Single-level

passenger area

Large deck

area

Modest

speed

Spacious

interior

Ride

comfort

Fuel

efficiency

All these

requirements point to a multihull with very long and very slender hulls

operating in displacement mode.

An asymmetrical

proa configuration is attractive because of the longer overall length for

reduced motions and better fuel efficiency, and for reduced cost due to the consolidation

of machinery into a single engine and driveline. However, figure A-4 shows that

in the power range under consideration, there is no significant machinery cost

saving available by using one large propulsion system instead of two smaller

ones. This is because the economies of scale have made diesel engine in the 300

hp range very inexpensive compared to smaller and larger power ratings.

Figure

A-4 Cost per brake horsepower (BHP) v.

horsepower

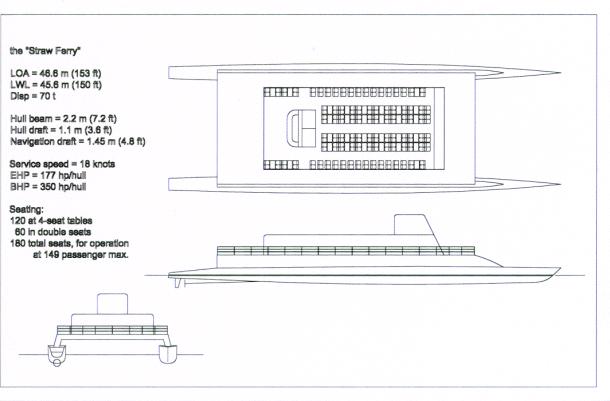

The vessel

proposed is a 149-passenger single-deck catamaran (with seats for 180) designed

to operate at a speed of 18 knots. It will be powered by two diesel engines of

approximately 350 hp each and operate with a crew of two.

18 knots is

relatively slow by modern standards, but it is fast enough to cover the 5.6

mile route in less than 20 minutes. This is barely enough time to buy a latte,

turn on the cell phone and open up the computer. That is, a faster trip will

not be any more saleable than the proposed 20-minute timing.

Fig A-5 The proposed conceptual ferry design

More

important is efficient ticketing and very fast loading and unloading. This will

have a greater effect on trip time than a few knots of additional speed. This

requirement dictates the open side decks, in addition to the deck areas forward

and aft of the passenger cabin. Whether moored bow-in or on a side tie, there

will be deck area to accommodate multible gangways.

Low hull

volume also dictates the very wide beam, necessary to meet stability requirements.

Emissions

controls will be similar to those used on modern busses. Because of the low

speed, the horsepower per seat is comparable to that found on a city transit

bus.

Location of the terminal

This

proposal calls for a ferry service that more closely resembles the service of

100 years ago. Rather than use the existing ferry dock inside the Marina, there

would be a new terminal in the open water alongside the Berkeley Fishing Pier.

This location has several compelling advantages:

1) It is

the closest to San Francisco. The 5.6-mile route will only take 20 minutes at a

modest speed of 17 knots. This is about a mile closer than other suggested locations

at the foot of Gilman Street or Fleming Point (behind the race track).

2) There

will be no wasted time maneuvering in and out of the Marina.

3) Little

or no dredging is required, unlike the foot of Gilman Street or at Fleming

Point that would require extensive dredging projects.

4) The

Berkeley Pier is at the end of the AC Transit 51 M bus line. Because this is the terminus of a major

trunk line, there is very frequent service (about every 20 minutes all day),

yet ridership is low because it is near the end of the line. It is a natural

location for an intermodal transfer. Rather than requiring new bus service,

this location would make use of existing excess capacity at the end of an

existing route.

5) There

are 410 parking spaces in the parking lot serving Hs. Lordships restaurant and

along Seawall Drive south of the Pier. These are mostly unused during the week.

Other overflow parking areas are nearby in the Marina. Peak demand hours for

ferry parking generally miss the peak demand periods for Marina parking, so

this would also take advantage of existing infrastructure rather than requiring

new facilities.

6) There is

existing nearby commercial activity (unlike the proposed Gilman Street

location, where commercial development is in question). Commercial activity

makes the ferry terminal a more attractive place to wait or to meet, and the

presence of the ferry is likely to increase public revenue from the nearby

businesses.

7) The

ferry route would not have to traverse any part of the Eastshore State Park.

Sierra Club and other groups have opposed commuter ferry service to any

location in Berkeley or Albany on the grounds that it would not be compatible

with the Eastshore State Park. The Berkeley Pier location is furthest from the

park boundaries, and does not traverse any park tidelands.

Figure A-6 The East Bay shoreline in 1883, showing the

ferry terminal at Jacob's Landing at the foot of University Avenue.

The Politics

The Sierra

Club is on record as strongly opposing a commuter ferry operating from anywhere

along the Berkeley or Albany waterfront. This opposition appears to be based

primarily on the prospect of a larger and faster ferry operating from the foot

of Gilman Street, an area that the Sierra Club hopes will eventually be

acquired by the State and become part of the Eastshore State Park.

These

considerations should have no relevance to the this proposal, which is well

removed from the Eastshore State Park land and tidelands.

Sierra Club

has, however, raised the objection to ferry-related traffic transiting the

Eastshore State Park on University Avenue. The numbers, however, don't support

the claim that this would cause a detectable qualitative change in the traffic

level. With a maximum capacity of 149 passengers and three departures every

morning, it is hard to imagine how the four lanes of University Avenue would

become congested. Considered in the context of the number of seats in existing

waterfront restaurants, activities at other Marina businesses and offices, and

the number of boat berths served by those same roads, the traffic argument

becomes specious.

If we

conservatively assume a capacity of 500 cars per hour per lane, and three full

ferries with every seat representing another car, then we have only used 26

minutes of road capacity for the entire morning commute.

On the

other hand, several interest groups can be expected to offer strong support for

a Berkeley ferry.

The bicycle

groups - East Bay Bicycle Coalition and Bicycle Friendly Berkeley - are ferry

advocates. BART is closed to bicycles during commute hours, while a ferry with

a large bicycle deck promises the efficiency of a true dual mode

personal/public transportation system.

Handicapped

advocacy groups are expected to show favorable interest. Ferries are spacious

and easy to use, and offer safe mobility for people with a wide range of

disabilities.

People who

like to travel with their dogs are likely to be strong ferry advocates. There

is no reason to preclude dogs from the outside deck areas of a ferry operating

on a short route.

As we have

seen from various public planning processes, the combination of bicycles, dogs,

and the handicapped comprises a formidable lobbying force. Even in Berkeley,

the Sierra Club would be ill advised to oppose it.

The Fare Structure

If we make

some very conservative assumptions about costs, the back-of-the-envelope

economic analysis suggests that the required break-even no-subsidy ticket price

is $6.28 each way. This covers vessel construction and operation, and assumes

2/3 full on the forward commute, 1/3 full on the reverse commute, seven round

trips per day, and about $400/hour for total operating expenses.

$6.28 is

steep, but this is less than the ticket price on the Vallejo ferries and comparable

to the $6.75 charged for the Sausalito and Tiburon ferries. It compares very favorably

with the cost of parking in downtown San Francisco for the day, or the cost of

a trip on an airport shuttle. As long as the boat is small and the service is

not too ambitious, there is probably a sustainable market at this price point.

However,

the market-rate ticket exposes the ferry proposal to charges of elitism, and

the criticism that the service is designed to serve only the rich. There is

some truth to these charges, so the strategy proposed here is to implement a

policy analogous to that in effect on the major toll bridges. On the bridges,

carpools go free. The rationale for this policy is that they tread lightly on

both the environment and the transportation infrastructure, and help alleviate

the congestion of single-occupancy vehicles.

On the

ferry, anyone arriving by bicycle and bringing it aboard would ride free. The

rationale is the same as on the bridges. This would insure that the ferry

remains accessible to the widest possible range of income levels, without

relying on public funds or complicated and inefficient subsidy schemes. It

would also immensely simplify ticketing and boarding for bicyclists.

This scheme

is of course experimental, and its success would depend on both its popularity

and the level of abuse that could not be prevented by the obvious

countermeasures. The free ride might have to be replaced by a deep discount

after some operational experience is obtained.

Discounts

would also be offered for the "reverse" commuters, SF to Berkeley in

the morning and westbound in the afternoon. Parking is scarce and expensive at

the San Francisco ferry terminal, so the discount could be justified on similar

environmental/infrastructure grounds, if not on simple supply and demand.

Reverse commute discounts would be extremely valuable to a significant number

of students at U.C. Berkeley, as well as some City employees

The Schedule

Because of

the low subsidy level, the schedule must be driven by cost and revenue

considerations. As long as there is a place to park at BART, the ferry can

never hope to compete with BART for level of service as measured in convenient

access to the terminals or stations.

But BART

parking lots fill up early in the morning. They are generally full by 8:00 am

on weekdays. Although a small number of spaces become available at 10:00, and

can be reliably accessed between 10:00 and 10:05, for all practical purposes

BART is not an easy option after 8:00 am. Certainly there are many people who

can walk, bike, or bus to the BART station. And while we acknowledge that these

people hold the moral high ground, for the majority of riders the only viable

means of travel to the station is access by private auto.

There is no

point, then, in scheduling a ferry departure before 8:00 am. With 20 minute

transit time an hourly schedule is feasible using one boat, so the proposed

morning departures would be at 8, 9, and 10.

After the

10 am departure it is assumed that the demand will fall below the level that

would support an hourly schedule. The problem becomes one of keeping the boat

busy during the mid-day lull. Assuming the crew's work day has started at 7:30,

the crew has only been on watch for three hours when the ferry is finished

unloading at the Ferry Building at 10:30.

We propose

the route topology shift from part of the 'hub and spokes" system centered

around SF to a circular route around the central bay, keeping the legs short

enough to be compatible with the relatively slow speed.

After

leaving the Ferry Building, the ferry would begin a clockwise circuit to

Sausalito, Tiburon, Larkspur and Richmond, returning to Berkeley in time for a 1:00

pm departure.

The next

loop would include a stop at Treasure Island, then SF, Sausalito, Tiburon,

Larkspur and Richmond, returning to Berkeley for a 4:30 pm departure.

The 4:30 pm

Berkeley departure would be in SF in time for a 5 pm return commuter run straight back to

Berkeley. Hourly departures would continue at 6, 7, and 8 pm.

The boat is

finished for the evening at 8:30 pm, and the crew could probably punch out at

9. This is a 13.5 hour day, presumably done as one 7:30 am 1:00 pm shift of 5.5 hours, and one 1:00 pm

- 9:00 pm shift of eight hours.

The mid-day

circular routes provide one trip from the East Bay to Treasure Island, and two

trips each to the three terminals in Marin. This would fill an important gap in

transit mobility, as there is currently no easy way to travel from the East Bay

to Marin.

Note that

there are four evening commuter return trims, but only three morning trips.

This apparent imbalance is to account for two factors: 1) a significant number of

morning commuters will be pulled away by informal carpools, attracted to the

HOV lane to the Bay Bridge. Although other transit agencies have resisted and

discouraged this practice, the ferry service should recognize the value of the

informal carpool phenomenon and accommodate it as much as possible. 2) There is

typically a much wider distribution of return times than departure times.

People work late, run errands, and have other reasons to delay their return

trip, suggesting the four-trip three-hour return window.

Here is

what the tabulated schedule might look like:

Treasure San

Berkeley

Island Francisco Sausalito

Tiburon Larkspur Richmond Berkeley

8:00 8:30 9:00

9:00 9:30 10:00

10:00

10:30 11:00 11:30

12:00 12:30 1:00

1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00

3:30 4:00 4:30

4:30 5:00 5:30

5:30 6:00 6:30

6:30 7:00 7:30

7:30 8:00 8:30

On the

other hand, the public might be better served by a simpler schedule, with

hourly service all day:

Berkeley

San Francisco Berkeley

8:00 8:30 9:00

9:00 9:30 10:00

10:00

10:30 11:00

11:00

11:30 12:00

12:00 12:30 1:00

1:00 1:30 2:00

2:00 2:30 3:00

3:00 3:30 4:00

4:00 4:30 5:00

5:00 5:30 6:00

6:00 6:30 7:00

7:00 7:30 8:00

Economics

Assumptions:

First cost

of ferry: $4 million (very conservative - other estimates are below $1.5 million

for a ferry that meets these capacity and speed specifications).

Operating

cost (crew, fuel, maintenance, admin): $400/hour (also conservative, probably based

on a crew of three).

Port fees

in San Francisco: $20,000/year.

Terminal

construction in Berkeley: $2 million (this is a wild guess, but probably

conservative if no breakwater construction is required).

Occupancy:

2/3 capacity

(99) full fare passengers on seven forward commutes.

1/3 capacity

(50) full fare passengers on seven reverse commutes.

1/3 capacity

(50) full fare passengers on one mid-day circle route.

12.5

operating hours/day, 255 commute days/year.

Calculations:

Total

fares/year = 255 x (149 x 7 x 2/3 + 149 x 7 x 1/3 + 149 x 1/3)

=

278,630 full fares/year.

Capitalization

= $6 million x 0.1 = $600,000/year.

Operation =

255 x 12.5 x 400 + $20,000 = $1,150,000/year.

Total =

$1,750,000/year.

Required

fare for unsubsidized break-even = $1,750,000/278,630

= $6.28.

Closing quote

"Nothing is impossible for the man who

doesn't have to do it himself."

A.H. Weiler