Ohel Yosef and Katamon TetTowards the southwestern outskirts of Jerusalem there is a string of old settlements outside the walls of the Old City. Most of this area was Arab prior to the 1948 war. Afterwards, the city expanded further as Jewish immigrants from North Africa and Iraq were resettled into new concrete blocks in the 1950s. Katamon Tet is the last of the "Katamon" neighborhoods. The worst part of this worst neighborhood is blocks 101 and 102. Built to accommodate typical European families with one or two children, they proved immediately inadequate to the needs of the extended families averaging 10 children who settled them, even after families were allocated blocks of two or three apartments each. Twenty years after being built, Blocks 101 and 102 were among the most studied "instant slums" in Israel. Typical of such blocks everywhere, the stairwells were public urinals, and lights were out on most landings. Poverty was severe. Public services, rare. By 1971 a special government commission had studied the problem and recommended billions of Israeli pounds in services and neighborhood fixes. It didn't happen. Then a guy named Aryeh Yitzhak showed up. This narrative was transcribed in April 1975:

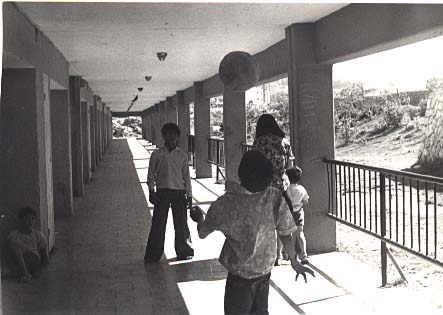

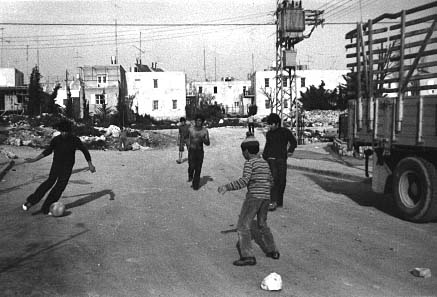

Be serious... there we were, everyday we'd go and stand around on the barzelim (street rails), shout a bit, and then go on home as usual. One day ... no, it was an afternoon, comes up some guy in a beard, a real down and outer we sez, an outcast from society, blah blah ... no wait, we had just come from work--now I remember, and we saw him sitting on the steps. Calls us over "C'mere," so we start talking about this or that--was right after the thing at Lod with those Japanese terrorists--or was it after Munich? ... No, I don't think it was after Lod ... anyway, some tragedy, so we're talking about the sad state of affairs and he sez well don't be sad--and the way he spoke! It's like he was from heaven--really amazed us ... so he sez, "hey, you wanna start a theatre group and what's a theatre group and most of us laughed at him, but three of us started with him in the beginning. First we did movements (show him what kind of movements, Eli, not just movements but you know stretching and ... crazy ... like yer hitting someone, but in the air) so we did these movements for eight months, like we worked for eight months on things we knew were crazy, but they weren't crazy, ya know ... then we began work on "Yosef yored katamona" (Joseph goes down to Katamon). Now "Yosef" was a whole angry trip. We lashed out at everything that was hurting us--the police, the poverty, our own peers--the whole society ... and people tried to stop us--our own parents called us liars. Teddy Kollek, the mayor, pretended to sleep during our first performance so people would think it was boring--but we kept showing it all over, and pretty soon people realized that there were slums, and that there was another Israel that wasn't all pretty and didn't sing "Jerusalem of Gold." The play, a simple, modern fairy tale, electrified the city with its stark and naïve portrayal of just what was wrong with the youth's neighborhood, Katamon Tet--not even the worst slum of Jerusalem. The plot was simple. The stage opens on a group of youths sitting in garbage cans. One of them, Joseph, gets up and says, "Friends, I'm leaving to find something better." His friends disagree. This is where they were born, and this is where they will die. For his rebellion, he is beaten up and sold to some passing Arabs. Now Joseph rises out of his can and finds himself in an Arab village to which the entire populace of Katamon Tet has been transferred. Neither the village nor Joseph recognize each other, and the people, upon seeing this youth rise from the garbage, take him for a God. Joseph then promises them a better future ... no more drugs, education for their children, television sets ... and all begins to come to pass until one day, two strangers arrive and tell the villagers who Joseph really is. Again he is beaten up, and next appears in jail, where he is raped. Next, his old friends are put in with him, and he exclaims: "Why didn't you believe me? Things can be better!" Finally in agreement, all march off as though the jail no longer existed, singing. The premier performance was nearly the play's last. The city withdrew support and demanded that the rape scene be removed. Parents took their children home and promised dire punishments if their offspring be seen near such pornography again. Well, look, at first we thought Aryeh [Yitzhak] was some sort of leftist. Then we worked with him for about 8 months and did "Yosef"; and we began talking with the audiences after performances, and began to see things from their questions that we hadn't realized, and we had already decided that the sequel would pertain to the problems of the society.... I think the important thing, though, is Ohel Yosef (Joseph's Tent), the moadon (youth center) we set up in a bomb shelter during the war. We gave a performance on the Golan, and one soldier asked us, "Nu, with all of this talk, what are you doing to solve the problem?" and it was during the war and there was no school, and the kids were running around on the streets, so we got permission to open a bomb shelter in Block 102. Michael Paran, a social worker who had the neighborhood beat helped us steal some equipment the city wasn't using, 'cuz they weren't giving us any help. And we brought some more from home and began activities with the kids and classes from the grown-ups in things like sewing and reading and writing ... but now that has problems, too, because it's all set up and became part of the institution. We're all drafted and we've run out of vision and the goals have disappeared, but still, I think it will continue. It has to.... Meanwhile, before the war, we had gotten together with some kids from Kiryat Hayovel, and the whole group had almost ended from petty quarrels--but about four of us stayed, and we decided to do a play about the way things really are with us--not just the bad, as we had done in "Yosef" but the good too. Then the war broke out, but six months later, we got back together and fashioned a series of skits around the barzelim, four guys who start to beat up on one of them and he flashes back to things like going to a café and behaving violently until the police are called ... and dreams too--there are songs like "The Green Land," about a green land, where we can be free and there's nature, return to God--good things, too. So we perform our play about 50 times at various community centers and schools, and a lot of times, we would just set up chairs at the Jerusalem Theatre to catch people after the regular performance--really get them around the neck--and show them what we had ... it's ... I really believe that it's important to show what you are--and that's what we were doing. I mean, there were some parts, like the skit with the bosses riding on the worker' back that were even harder than things in "Yosef", but the point was that we showed good things, too--we wanted them to understand just what we were. At one of the performances was a representative of the German drama Festival that's held every two years, and he asked us to represent Israel. The group broke up last April because so many people were drafted, but we agreed to go if it came off; and last September they got back in touch with us, and in October was the Festival and we got releases from the army and we went. We took second place, as a matter of fact. Okay, so that was that, and about two months ago, we began working on a new script--that is, the people who are still in the group. We all have replacements because of the army and who is home on leave, but it's progressing. Moshe [Salah]--hey, you were at his 18th birthday party the other night--Moshe wrote all of the music, and Nafi, his brother, is directing it. It's ... it's about us ... our problems in setting up Ohel Yosef. We called it "Partly Cloudy," because things aren't so good--but they're not really so bad, either. In it, we describe the problems we had in setting it up--the parents who thought we were all delinquents and didn't want their kids near us; the people who promised to help us, gave us keys to the bomb shelter, and then disappeared; the troubles with the neighborhood tchakh-tchakhim (greasers) when we tried to get their support--even the trouble amongst us--like who wanted to do all of the work? And the whole point is that we want to show this to other neighborhoods, to show that they can do it too. I mean, I don't know what our goal is as a theatre group ... people drop out, go into the army, new people join but what we're doing now is the direct product of what we have been doing in the neighborhood trying to improve things--and don't think that just because we've begun things are so much better. We've got some activities for the kids, help them with their homework, some arts and crafts, field trips, but we're still poor, and we're still crowded, and we still have criminals growing up out of the streets.... The thing is, we're going to keep doing these things, still putting on our play--and hopefully, the people in other neighborhoods will see that it can be done--I mean, we show them right in the play--take a bomb shelter, paint it, get old pictures form home--chairs, ... tables, maybe a ball--that's all that it takes ... and we show the problems with the people--the way, here we are, the most downtrodden people; and we're also the most passive, the most accepting of our lot--and that's gotta change, damn it.... Maybe it's egotistical of us. Maybe we should be helping serve the army--instead of going AWOL to work with the kids like Moshe did. He spent a month in jail for that trick.... But if we don't do these things who will? The City? They wouldn't even give us equipment to set up our moadon (youth club) at first ... and we want to start a newspaper. A newspaper is something important (ha ha! He's going to write that in his newspaper) ... and we want so many things ... Okay, ya'alla, I have to be up at five in the morning to get back to my base.... Appendix: Photographs of Katamon TetPhotographs taken by Block 102 resident, Yamin Mesika, exhibited at the Lown Community Center, Kiryat Hayovel, Jerusalem, reception, 12/31/75. At the time, he was 18 years old and serving in the Israeli Army. Yamin was the original "Yosef" in the theatre group's first play.

|