|

Judy Malloy: A writer's notebook is not a final paper but rather reflects the development of a work, in this case a work of electronic literature. In the informal yet productive practice of creating notebooks online, ideas and sources are developed and slowly emerge.

C onsidering the role of online notebooks in the creation of one writer's work is an appropriate closure for this writer's notebook that accompanies The Not Yet Named Jig, . Often begun as artists books, each of the print notebooks, that I kept as a central part of my work before I began writing notebooks online in 2009, gradually evolved as a repository for cryptic notes about the creation of world models, stray code for authoring systems, and superseded explorations of evolving interfaces -- interspersed with details of life, such as uncompleted todo lists and telephone numbers of friends and acquaintances. From an historic point of view, whether or not there is a gain in information about writers' lives in online notebooks depends on if you are interested in shopping lists, dates of lunches with friends, and the unguarded opinions that pepper writers' print notebooks or whether a writer's filtered thoughts (seldom expressed anywhere else) are of value. Contingently, I have found that keeping an online notebook forces a more comprehensive thinking about the work I am creating. This is a primariy reason for spending time creating an Internet-based writer's notebook.

Conversely, there is a potent, tangible "objectness" to print notebooks.

However, there are intangible qualities in online notebooks that may not be so obvious in print notebooks -- for instance how to a certain extent our lives merge with the lives of the characters we are writing; how the images and texts in online notebooks subtly reflect this; and how the edited writing necessary in online notebooks distills our thoughts and keeps us on a path, where an understanding of the vision that informs our work is central. Because my work initially centered on artists books, even in the throes of keeping an online notebook, I have often simultaneously kept a print notebook in which to paste scores, write cryptic notes about as yet constructed world models, record appointments and lunches with friends. But this year with the conjunction of the pleasurable activities of teaching electronic literature and writing and receiving chapters for my MIT Press book, Social Media Archeology and Poetics, and with the intense process of writing lexias for The Not Yet Named Jig, there was not time to keep a print notebook. Thus, as the year ends, I have no print notebook to hold in my hands as a tangible record of the autumn of 2014 in Princeton. The images that float beside this text are from a previous print notebook. Perhaps, at this point, it should be noted that despite the prevalence of the computer screen as a writing substrate, some writers continue to carefully compose daily print notebook entries. Years later, we will find out who they are. (and envy the photographed presence of their notebooks, as they appear in the Twitter accounts of respected institutional archives.) T his week for the Introduction to Social Media Archeology and Poetics, among other things, I am looking at the model of the environment where Will Crowther's Adventure and mailing lists on food, wine, and science fiction existed side by side (although not always uncontested) with ARPANET research. Additionally, in the early 1970's, the online conferencing -- that for instance accompanied the creation of FTP -- was influential in early Internet-based social media, while, at the same time, a plethora of RFC's (Requests for Comment) not only shared the process but also ultimately served to document the roles of researchers. Contingently, in our contemporary Internet era, when writers and artists record the creation of their work -- whether it is through Twitter or Facebook or an online writer's notebook -- our words and images contribute not only to the development of our work as writers and poets but also to the cultural environment of the Internet.

With these thoughts I am reminded that the remainder of this holiday is dedicated to Social Media Archeology and Poetics, while at the same time it might be good to record that Friday I took time for a picnic in the woods. Saturday was an adventure in small town in New Jersey, and this coming week, I look forward to a visit with family. Writer's notebooks -- both print and online -- for the coda to my work of public literature, From Ireland with Letters, will begin in late January, 2015.

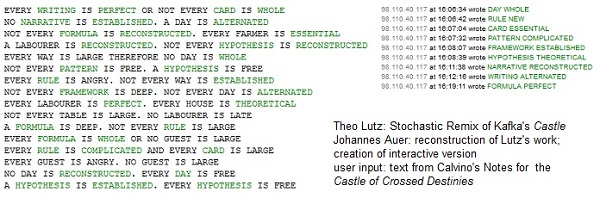

A s the year winds down, so does this 2014 writer's notebook, written in Princeton during the creation of The Not Yet Named Jig, a generative hypertext that is Part VII of From Ireland with Letters. The Not Yet Named Jig is not completely finished. In addition to editing, it needs about 20 more lexias, and some tweaking of the authoring system. However, the point has been reached, where it is productive to withdraw from immersion in this work and set it aside for a while. Usually at this point, I line up an exhibition for the work, so that in a few months I will be forced to revisit it in terms of a completed work. In 2015 a new notebook will begin the writing and structuring of the unmeasured polyphonic coda that will conclude From Ireland with Letters. M eanwhile, as a holiday break, I have begun the handmade work of information art, described in the December 8 entry in this notebook and this week named Every look is far. No way is silent from a random sequence in Theo Lutz' Stochastische Texte.

Every look is far. No way is silent is a project to work on from now until the summer. It will require about 200 separate small manuscripts that will be printed and then (based somewhat on the Medieval Chaunce of the Dyse) rolled up and tied with gold string. The project will also require a painted bucket to hold the manuscripts and a generative database of the words. A reoccurring image on the "manuscripts" will be The Lagado Machine which Jonathan Swift described in Gulliver's Travels in 1726. In this holiday week, as a series of enjoyable breaks from working on the Introduction to Social Media Archeology and Poetics, two draft manuscripts for Every look is far. No way is silent were created. The first contains text from Christopher Strachey's Paper, "The 'Thinking' Machine". (Encounter, October 1954, pp. 25-31) The second contains text from Jasia Reichardt's introduction to the catalog for the 1968 seminal London ICA exhibition, Cybernetic Serendipity. Eventually, many more texts and faces from the electronic literature community will appear on in the center and on the borders of these manuscripts. But, it is now time to return to the Introduction to Social Media Archeology and Poetics. In May of this year, Vint Cerf kindly talked with me about the beginnings of the Internet and set forth the relationship of this collaborative development process to the development of early social media. It is a pleasure to review his words.

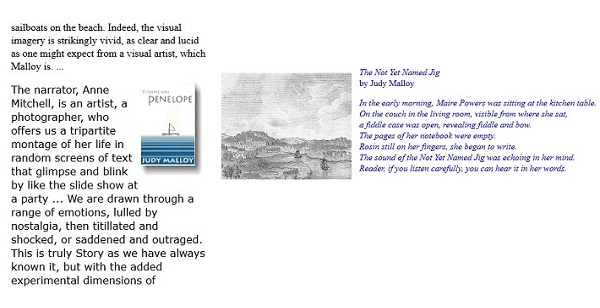

V isiting/revisiting early papers in computer-mediated narrative -- this week in an early paper by Natalie Dehn: "Story Generation after TALE-SPIN" [1] -- I explored differences in approaches to the role of the computer and the role of the writer in the creation of electronic literature. [2] 1. Assumptions about authorial practice in "Story Generation after TALE-SPIN" illustrate the need to explore the myriad of differing visions of authorial practice when conceiving programs in which the computer simulates the storyteller. 2. In a contrasting approach to computer-mediated narrative, when, in the introduction to the Eastgate its name was Penelope, I wrote: "The reader of its name was Penelope is invited to step into Anne's mind, to see things as she sees them, to observe her memories come and go, in a natural, non-sequential manner." I meant that the use of computer-mediated generative hyperfiction enabled the telling of a story in which the reader experiences the memories and thoughts of the narrator in a way that would not be possible in print literature. Despite the challenging words I wrote in the passage that introduces this notebook entry, in my own work, I have never wanted the computer to be the storyteller. 3. There are surprising ideas about how writers work in Dehn's approach. For instance, she does not believe that writers begin by creating a comprehensive world model but rather that details emerge on the fly to suit the needs of a writer's plot. Perhaps this is not important if the program she conceives is meant to simulate her own thinking as a writer. But -- and this was underscored by the fascinating talk which graphic interactive fiction pioneer, Jane Jensen gave to our Princeton electronic literature class last week, in which she discussed how the rich details of "room" and character in Gabriel Knight were created and recreated -- I doubt if I am the only writer who (before I begin the actual writing) constructs a detailed world model which includes not only the setting but also many details of the characters' lives, even though some of these details may never be divulged to the reader.

5. It should be remembered that Natalie Dehn's "Story Generation After TALE-SPIN" was an important paper in AI approaches to computer-mediated narrative. In Of Two Minds, there are aspects of her process that Michael Joyce credits in the development of his own work, for instance "'..the dual, directed-yet-serendipitous, nature of creative thinking...'" [4] 1. Natalie Dehn: "Story Generation after TALE-SPIN", IJCAI'81, Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial intelligence, v. 1 pp 16-18 2. In sardonic response, Sara Roberts' challenging AI history-influenced Early Programming is unforgettable. "In it the visitor sits down at a kitchen table with a computer 'mom', (named MARGO), and is recruited, if not forced, into the role of a child". See Anna Couey and Judy Malloy, "A Conversation with Sara Roberts on the Interactive Art Conference on Arts Wire, June 1996 3. James Meehan, "TALE-SPIN, An Interactive Program that Writes Stories", Proceedings of the Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 1:91-98, 1977. 4. In Of Two Minds, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995 p. 167) Michael Joyce quotes these words from Dehn's "Story Generation after TALE-SPIN".

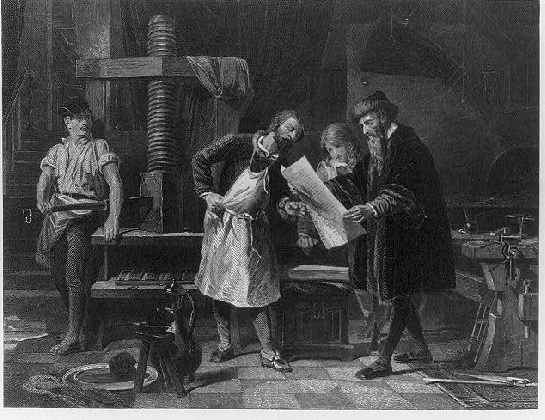

B uilding on plans described earlier in this notebook, in this cold, rainy week, I am working on beginning a small information-containing object to respond to challenging issues that the 2015 ELO Conference and its provocative title ("The End(s) of Electronic Literature") raise about the future of electronic literature. In the conceptual foreground are words that the electronic literature community has written about electronic literature (past, present and future) and how our words elucidate the lineage of electronic literature and point to the future of the field. In the conceptual background is the way that print literature and electronic literature echo, inform and inspire each other -- in our own work, in the work of our colleagues, in our lineage. In this case the contingencies between the aleatoric medieval manuscript The Chaunce of the Dyse and Free Values, a work I created in 1988 while considering the bridge between such medieval aleatoric manuscripts and the writing of generative hyperfiction. In this case, Pulskamp and Otero's recent documentation of Wibold's 10th century Ludus Regularis and an interest in the experience of the (diceless) user in the reader-mediated "grab bag" interface (such as I used in the web version of Uncle Roger File 3) versus the seemingly more magical reader-passive, computer-mediated random production of lexias. The exact image for this project has not yet materialized. Meanwhile, the Fry & Co. 1869 steel engraving -- "Invention of Printing - Gutenberg Taking the First Proof" (from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division) raises issues of the changing technologies of conveying the written word. Preliminary Documentation is as follows: Continuing a theme that has been central to my work as an editor in the field, beginning with the "Words on Works" section that I created for Leonardo in the early 1990's -- this work will be based on the words of writer's and critics of electronic literature. Continuing with the concept of information as an artist's material, (first expressed on the Internet in Making Art Online) this work will explore electronic literature though the words of its creators and critics.

E choing the number of entries in The Chaunce of the Dyse, 56 statements will be collected and each printed as many times as needed for the situation. Each small manuscript will then be rolled up and tied with decorative string, so that the words inside are not visible. A bucket to contain the statements will be painted and lettered with something to the effect of

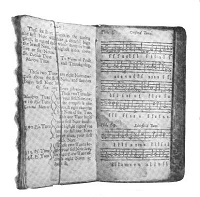

"The Past, Present and Future of Electronic Literature. The manuscripts will then be placed in the bucket. (which will need to be refilled from provided stock as needed) A generative version of the entire database will also be available online. Background (from previous notebook entries) 1."Time travelling in the history of electronic literature, this week in the 10th Century in Medieval France, I encountered Wibold, the archdeacon of Noyon, who hacked dice to turn gambling (forbidden to clerics) into a dice-generated game of acquiring of virtues. "it is very appropriate that having abandoned vices according to the [canonical] rule, [clerics] cast lots for themselves in order to acquire virtues," he noted, according to Richard Pulskamp and Daniel Otero, "Wibold's Ludus Regularis", a 10th Century Board Game, Loci, June, July 2014. (hosted on the website of the Mathematical Association of America) In this prequel to The Chaunce of the Dyse, the cleric possessing the most virtues was the winner. The authoring strategy, described in detail in Pulskamp and Otero's paper, included imprinting the dice with letters." (September 20-21, 2014) 2. "In my current understanding, The Chaunce of the Dyse (MS Fairfax 16 and MS Bodley 638) consists of three introductory stanzas and 56 short narratives, keyed by combinations of the throw of dice. When the game was played, a master of ceremonies read the poetry that introduced this literary game. Each player rolled the dice three times to key the results to a text. The player then read aloud the text assigned to him or her. Based on then relatively contemporary works, such as Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, texts were personal, satirical, literary, character building, character destroying, embarrassing, pleasing." (September 7, 2014) In Ethics and Eventfulness in Middle English Literature, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009) J. Allan Mitchell observes that "The Chaunce of the Dyse haphazardly throws up allusions, attempting by chance to close the gap between literature and life, past and present, 'game' and 'ernest'. This is the way the game produces, for a coterie of readers, the conditions of possibility for events to happen that confer unforeseen meanings on literary experience, respectively and prospectively." (pp. 63-64)

....On Friday morning, there was snow on the ground as I walked across a Princeton hillside. When I arrived home, a copy of John Rosenberg's Dorothy Richardson, A Critical Biography was waiting on the stairs outside my door. In it was the full quote I had been looking for to begin the documentation for The Not Yet Named Jig: O n Sunday, it was a pleasure to spend time with the theory history, and practice of the seminal BBS, THE THING. In their chapter, Berlin-based new media critic Susanne Gerber and Founding Sysop, Wolfgang Staehle, intertwine essay, interview, and multi-page timeline, and in the process innovatively document THE THING -- beginning with the "crossing-over" of art history and media history in the founding of THE THING in November 1991 in a Tribeca basement. Monday was an enjoyable American Studies Fellows luncheon with Program Manager Judith Ferszt, and fellow Californians: historian and labor photographer Richard Street, and environmental historian and writer, Jenny Price.

On Tuesday, in Electronic Literature: Lineage Theory and Contemporary Practice, we explored gender and identity in electronic literature -- beginning both with commemorating Leslie Feinberg's death with a student's immersive, empathetic Inform7 adaptation of the letter in Stone Butch Blues and with remembering lives of African Americans with Wendel White's evocative web work, Small Towns, Black Lives -- and concluding with Marco Williams' challenging Interactive Fiction, The Migrant Trail. Afterwards, the students went on holiday with classics of electronic literature criticism and documentation from my own library. (or perhaps left these volumes in their dorms for future study) At home on Wednesday I wrote a series of new lexias for The Not Yet Named Jig, while outdoors, in the midst of this busy, creative week of Thanksgiving, the weather in Princeton turned from the crisp air of late fall to rain and snow and slush. O n Thanksgiving morning, there was a dusting of snow on the pine trees visible out my window. The weather was conducive to a holiday weekend devoted to a review of papers received for Social Media Archeology and Poetics. (MIT Press, 2016) And -- as new papers arrived by email and in-process papers were returned with approved edits -- the early history of social media continued to come alive in the words of those who created and documented the field.

Papers on my laptop for the long weekend are:

Community Memory -- The First Public-Access Social Media System

alt.hypertext: an Early Social Medium

Art and Minitel in France in the '80s "From the very beginning, and during a few years, the Minitel has been the territory of art projects and art experiments. With a few exceptions, what remains of those artworks, created mostly between 1982 and 1988, is traces, residue and documentation. The process to discover, collect and analyze those fragments in order to elaborate their history has just started. At the time of writing (November 2014), I have identified 73 projects created under the umbrella of the online magazine-gallery ART ACCES Revue and 33 artworks carried independently by 8 artists or groups of artists."

IN.S.OMNIA, 1983-1993

"Surely what fiction, at the its best, can do, is to arrange data, truths in their real relationship by a process of selection. Like an artist making a picture. Something akin happens to us all as we get on in life. We see data of experience no longer chronologically, but rearranged in their true sequence. The past comes at last to life, transformed, rearranged, immortal." - Dorothy Richardson (quoted in John Rosenberg, Dorothy Richardson, A Critical Biography. NY:Knopf, 1973. pp. 155-156.

I n the Princeton woods, the recollection of autumn lingers in the cold November air. It is time for cocoa or hot cider with cinnamon, and ahh -- finally an about file for The Not Yet Named Jig has begun. If the act of attaching it to the opening page was satisfactory, the realization of many words not yet written was disturbing. Nevertheless, there is a beginning: O n the morning of April 24, 1660, the background for the story of Walter Power and Trial Shepard emerges in fleeting descriptions of their lives and environment -- produced at the will of the computer in The Not Yet Named Jig. Created with generative hyperfiction, the world model of a time and place over 350 years ago is surprising.

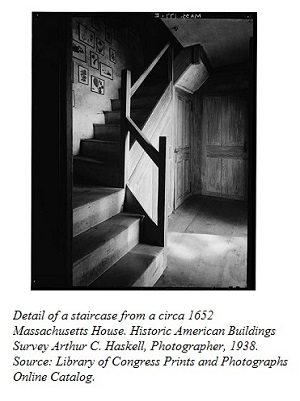

The decision to move from the polychoral composition (both measured and unmeasured) with which the larger part of From Ireland with Letters was composed, was partially made because of the need for a change of pace in this next to final part. But the primary question was: How could I create a truth-laden world model of a time and place -- the community of Malden in The Massachusetts Bay Area Colony in 1660 -- when many details were simply not available? The answer was to carefully write all the known details into lexias, fictionalize narrative only when necessary, and allow the computer to bring up the lexias at will. And so, returning to the authoring system I developed for the third file of Uncle Roger in 1987-1988 and tweaked for its name was Penelope, beginning in 1988, the lexias for the Not Yet Named Jig appear at the will of the computer, one at a time, or in pages of five.

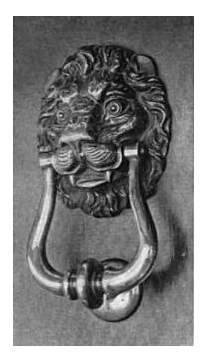

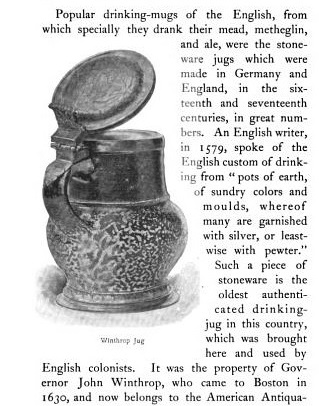

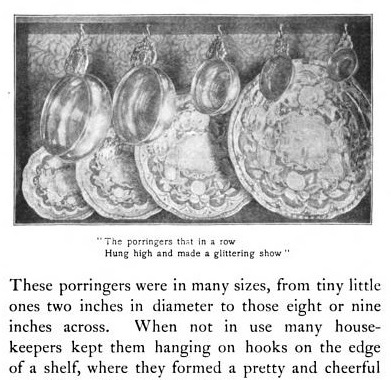

F rom only the images I have been assembling -- with the possibility of inserting them into the text of The Not Yet Named Jig -- stories could be inferred, written/rewritten. Italo Calvino, of course, has already done this in The Castle of Crossed Destinies, the text that Cliff Wulfman selected as a class discussion to follow my presentation of certain works of electronic literature that function as electronic manuscripts. (an update of the Authoring Software documentation of The Electronic Manuscript) Triggered by The Castle of Crossed Destinies, by the potent image of the door knocker on Ralph Shepard's door in The Not Yet Named Jig, and by the four iconic images above, I returned this week to the output of James Meehan's TALE-SPIN, an early interactive/generative fiction hybrid that generated animal stories in response to reader input. If approached as electronic literature, the output of Meehan's TALE-SPIN leaves much to be desired. No matter how interesting the algorithms, interactive art -- a hybrid of the creative endeavor of artists and programmers -- is ultimately only as effective as its content. Indeed, I see no need to repeat the output of TALE-SPIN here. Examples are included in Meehan's paper "TALE-SPIN, An Interactive Program that Writes Stories", Proceedings of the Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 1:91-98, 1977. N evertheless, Meehan created an authoring system that has maintained its relevance many years later. Worthy of continuing consideration are his prescient hybrid of generative and interactive literature; the early realization of the dual roles of the programmer and the reader; and algorithmic solutions to issues including cause and effect, narrative problem solving, character movement, mapping, relationships between characters, and character motivation. "TALE-SPIN starts a story by creating a problem for the main character, drawn from the four sigma-states mentioned earlier. Many subproblems may be encountered on the way, and there can be side-effects that are problems that need solving as well. The degree of difficulty is in part demined by the user. In specifying how one character gets along with another, he can make the problem harder to solve, which also makes the story longer..." -- Meehan p. 96. Additionally, heralding a contemporary era of evolving literary practice, although Meehan begins centuries earlier with Aesop, TALE-SPIN echoes the example-laden lessons of the medieval bestiaries that bridged the gap between oral and print literature.

The "sigma-states" which Meehan places at the core of TALE-SPIN are: F riday afternoon in the Chancellor's Green Rotunda at Princeton, an extraordinary program honored Princeton Professor of Creative Writing Joyce Carol Oates and twelve of her former students, including Jonathan Safran Foer. With two consecutive panels, the program explored the role of a dedicated professor and master writer in the lives of writers -- and in the process was invaluable for both students and professors of creative writing.

E lectronic literature is an interactive field, where professors challenge students, and in response, students challenge professors with their innovative works that not only refer to both classic and new works but also reflect individual vision. The midterm projects we received for the Princeton University seminar on Electronic Literature: Lineage, Theory and Contemporary Practice are interesting, challenging, surprising, wonderful, unusual. The names of the students, along with their projects and/or documentation will be available at the end of the semester, (which at Princeton is not until late January) as is traditional. Meanwhile, I note that Midterm projects in this class included:

Three different approaches to hypertext literature

Three different approaches to Interactive Fiction

Images -- the cover of a book, the opening screens of a work of public literature, the 16th century door knocker, brought from London by the Shepard family, symbolically key narratives. The British lion, that once adorned the door to the home of Ralph Shepard's grandfather, is also a reminder of the origins of the family into which Irish slave Walter Powers marries in 1661. Beginning with the British door knocker, (which the Shepard children regard with wonder and decorate with flowers on May Day) I replayed The Not Yet Named Jig. Afterwards, into the code I reentered the green banner emblazoned with a golden harp that the men in the Power family carried into battle in 1649. And then I increased the odds of the following words by Tecumseh appearing in the story, by reentering them in the program:

"Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mohican, the Pokanoket,

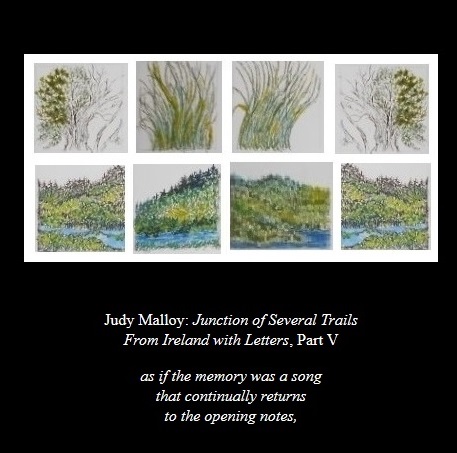

It could be imagined, I note -- as I look at autumn images of different trails through the Princeton woods -- that some trails are "measured notation". These trails are all different but with certain common features, such as a clearly defined paved or semi-paved road, such as a feeling that you think you know where they lead to, such as the way, the forest proceeds in an orderly way along the road. Other trails are "unmeasured notation". On these trails, the path is paved only with disorderly fallen leaves; at times the forest merges with the trail; unless you have walked this way before, you do not know what to expect. But on the day of the images above, I followed an unmeasured trail that (I was aware) concealed (at its entrance) a disconcerting recursive looping. On the way back, I stopped at the paved trail in the image above but did not follow it, although I do not know where it leads. And some trails are not recorded in this notebook because they are too beautiful or too fragile. None of these metaphors are explicit as regards the issue of the writing of polychoral literature in measured or unmeasured notation, nor are they intended to be so. Furthermore, the initial images have been changed several times since I wrote the words above. On November 3, images from that day were included; on November 4, the images reverted to the original arrangement. On November 9, there were only two images. But by the end of the day, I had echoed the first image. In the cold air of late November, an October recollection caused six preludes to appear. As Davitt Moroney observes in his 1976 paper, "The Performance of Unmeasured Harpsichord Preludes": "Good prelude playing requires the invigoration of imaginative freedom, but the player must be liberally inclined to impose on the music that measurement and shape which his imagination dictates." (Early Music 4:2, April 1976 p 143-151) I was also intrigued by the quote (partially reproduced below) from Chapter Nine of C.S. Lewis' The Magicians Nephew, which Philip Chih-Cheng Chang uses to begin his 2011 thesis on Analytical and Performative Issues in Selected Unmeasured Preludes by Louis Couperin: "...she was beginning to see the connection between the music and the things that were happening. When a line of dark firs sprang up on a ridge about a hundred yards away she felt that they were connected with a series of deep, prolonged notes which the Lion had sung a second before....." Like last Sunday's discovered but unfollowed trail, I have not yet read Philip Chih-Cheng Chang's thesis, which I will read and cite more thoroughly, as soon as I read the new chapters that have arrived for Social Media Archeology and Poetics.

"In the creation of interface. I work somewhat like a painter, who maintains his or her original vision in a series of works, while at the same time somewhat varying each work as the series progresses. And within each larger narrative, there may be variations of structure." As the lexias in The Not Yet Named Jig progress to the point that editing, tooling up the program, and addressing screen design will begin soon, I look ahead to the decision of how to write and structure the conclusion to From Ireland with Letters It has been a long journey from March 17, 2010, when this work began. To review, From Ireland began with three parts written in unmeasured notation. (The Prologue, Begin with the Arrival, and passage) In the summer of 2012, after the first three parts premiered in my Retrospective at the 2012 Electronic Literature Organization Conference and Internationally at the Electronic Language International Festival in Brazil, I wrote part four, fiddler's passage, using a new system of measured notation that I called fiddlers_passage. The next two parts, Junction of Several Trails and Gone With Our Wanderers, were written with this measured notation authoring system. However, as the story shifted to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century, where what precisely happened was unknown, in the summer of 2014, I returned to the generative hypertext of its name was Penelope to create part seven, The Not Yet Named Jig. This week, looking ahead to the final part -- where the story will move back to the relationship between Irish fiddler Máire Powers and Art History professor, Liam O'Brien -- I am considering a return to unmeasured notation. The closest to the authoring system I am seeking is the Third file of Paths of Memory and Painting, in which the authoring system, loosely based on the trio sonata, creates a duet between two major parts, and the third part is a basso continuo. In the final part of From Ireland with Letters, the basso will consist of small rhythmic details from the romance of Walter Power and Trial Shepard, while in counterpart, the duet will be the thoughts and actions of Máire Powers and Art History professor, Liam O'Brien, on their trip to the site of Walter and Trial's homestead. In the next month or so, in addition to continuing to write lexias for The Not Yet Named Jig, I look forward to revisiting the differences between measured and unmeasured notation in electronic literature.

October 19, 2014

T he soft colors of the grass in a small woods west of Princeton dominated the walking experience last week. This week, pale yellow trees above and the rustle of leaves on the ground retold the experience, as I passed through this same woods on the same trail at the same time of day. In this way -- as autumn gradually changes the colors of the woods -- in the slow process of writing lexias, a picture of life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1660 emerges in the generative hyperfiction The Not Yet Named Jig. And once again I am amazed at what the process discloses. Generative hyperfiction was used in its name was Penelope to create a whole picture of a photographer's life by accumulating details as seen through her own eyes. In The Not Yet Named Jig, it is used to create a world model of a certain place at a certain time by accumulating historic details of the people and the environment in which they lived. The writing is intense and difficult, requiring with each added lexia, a constant replaying/rewriting until the narrative works. Yet every time a five-lexia page is built and rebuilt, the story becomes clearer. What seems to be important is that an imposed authorial structure is not shaping how the story emerges for the reader. Last week in Electronic Literature Lineage, Theory, and Contemporary Practice at Princeton, students presented their in depth, critical and innovative traversals of hypertext literature, including works by Michael Joyce, Stuart Moulthrop, Shelley Jackson, Deena Larsen; and MD Coverley, as well as two relatively recent works: Mark Marino's a show of hands (created in Literatronic) and Dan Waber's a kiss. (created in Twine) Many of these works are densely constructed with hundreds of lexias that at times do not behave in expected ways, and rather than seeking treasure objects, (as in Interactive Fiction) the reader's quest in hypertext literature centers on the discovery of meaning in the woven narrative. Last week's scholarly student explorations of this rich material focused on issues of content in relationship to hypertextual shaping of the reader experience. In electronic literature, where each reader invariably emerges with a different perspective, student presentations continue to educate the class as a whole, including the professors. Returning to generative literature, (covered in the opening lectures on authoring systems and early electronic literature) my short lecture/exploration on "closure was never a goal..." in contemporary works of generative literature followed the student presentations of hypertext literature. Of particular interest was the way JR Carpenter's Along the Briny Beach (one of the remixes of Nick Montfort's legendary JS Taroko Gorge) functions, in her words, as "a coastline generator". The work is composed in such a way that a rewrite of Nick's original code plays vertically on the left, ("drive along the briny fabled wave-washed unnamed"; "Far shore copyrights the wave actions") while in the foreground images and poetry appear and disappear in a horizontal flow. The experience of Along the Briny Beach is enhanced by exploring JR's literate code -- with its inclusion of "charlesdarwin" variables ("Atmospheric Dust - Habits of a Sea-slug and Cuttle-fish - Rocks, non-volcanic - Singular Incrustations....") and the entire text of Lewis Carroll's The Walrus and the Carpenter. ( "The sun was shining on the sea, Shining with all his might....") T he issue of user interface in classic hyperfiction as opposed to what we are accustomed on the World Wide Web, recalls (in retrospect) Jeff Raskin's observation that interface design tends to be driven by what the user is accustomed to using. However, there are times when designing for natural and intuitive interfaces can be detrimental -- i.e. there is a conflict between creating an interface that actually works better (or expresses an artist's vision better) and creating an interface that the user is accustomed to using.

____________________________________________________

October 12, 2014

"Of these events, Muse, daughter of Zeus, C onfronting the need for documentation of The Not Yet named Jig, including generative hyperfiction as a genre, I began last week with an initial exploration of papers from the French generative poetry school,[1,2] and with my own documentation of how in 1988 I turned from the hypertexual authoring in the first two files of Uncle Roger to the generative hypertext authoring in the third file and, in the same year, began to use generative hypertext authoring to create its name was Penelope. "The literary device is conceived as a homogeneous whole computing device from writing to reading. Consequently, the running of program in real time at reading is an intrinsic moment of the work: the program of a work cannot be reduced to its algorithmic dimension. The running time is the embodiment of the work. Running gives to the work its sensual side." -- Phillipe Bootz, "From OULIPO to Transitoire Observable The Evolution of French Digital Poetry". At this time, my goals are to create an "about" file for The Not Yet Named Jig, as well as to compare different observations and to collect sources for future study. As an initial observation, I note that a characteristic of generative hypernarrative is that -- rather than permutating words in sentences and randomly displaying these sentences in endless runs -- generative hypernarrative, as I have used it, is created with a database of whole lexias. These lexias, (intuitively but not explicitly linked) are displayed at random. [3] It is not that classic generative poetry is not evocative/wonderful/innovative. Indeed, in the hands of master poets, generative poetry can be surprisingly brilliant/emotion-laden. In addition to the work of Jean-Pierre Balpe and Phillipe Bootz, I am thinking of Alison Knowles' House of Dust and Dick Higgins: Hank and Mary, A Love Story, a Chorale. However, generative hyperfiction strives to create a different kind of computer-mediated literature, a work of fiction or poetry that simulates the way memories come and go in our minds and/or creates a world model from carefully composed, contingent fragments. As I wrote in my classic Uncle Roger paper: "The rapid-fire" random production of records used in this final file simulates the diffuse, unsettling quality of contemporary life, as experienced in the narrator's mind." [4] ________________________________________________________________

1. Balpe, Jean-Pierre,

"Principles and Processes of Generative Literature: Questions to Literature", Dictung-Digital, 2005 ________________________________________________________________ C lassroom experiences can elucidate eras; in seminar situations, students bring important new perspectives. Last week in Electronic Literature: Lineage, Theory, and Contemporary Practice, Princeton students traversed works of classic and contemporary Interactive Fiction, (Perec, Infocom, Plotkin, Short, Reed, and Leishman) interspersed with discussion. Following a brief break, my colleague, Cliff Wulfman, deftly explored hypertext history and theory, and in response, I explored narrative, interface, and artists' words about their works, including Uncle Roger, afternoon, Victory Garden, Quibbling, Forward Anywhere and a show of hands. (Malloy, Joyce, Moulthrop, Guyer, Malloy and Marshall, Marino) "...A lake with many coves is how I saw it. The coves being where we focused, where individuals exist, where things are at least partly comprehensible: the lake being none of that, but naturally more than the sum of the coves, or more than what connects them" [5] ________________________________________________________________ 5. Guyer, Carolyn, "Quibbling: A Hyperfiction", Leonardo, 26:3, 258, 1993, ________________________________________________________________ In this intense class that explored the differences between the two genres, while at the same time introducing classics in both genres, the progression from Interactive Fiction to Hyperfiction was fascinating.

October 5, 2014

A Sunday walk along a brook in Princeton

It is not widely known that Carl came from a background of studying 19th Century French painting. He liked to fish in mountain streams. He got NEA funding for the project that a filmmaker and I did in 1978, for which we created a series of artists books, videos, and maps of an acre in the redwoods above Berkeley and placed them on the shelves of a San Francisco Public Library. Perhaps there is another point here: that like Andy Warhol, Carl Loeffler thought that contemporary art was not necessarily one thing or another. B eginning with the overflow crowd at the opening of the new Digital Humanities Center at Princeton -- continuing with the reading of Lee Felsenstein's paper (for Social Media Archeology and Poetics) on The Community Memory, continuing with a revisiting of classic hyperfiction; continuing with my semi-annual webstat review (that as usual revealed that there is a public who reads electronic literature) and finishing with the reading of Jamie Blustein and Ann-Barbara Graff's paper on alt.hypertext, the Usenet group where Tim Berners-Lee announced the World Wide Web -- this week many things occurred, from which the idea of remembering the reading public resurfaced.

Following one's own vision is vitally important for a writer. The issue is not that contemporary artists should tailor their work to perceived public taste; the issue is that sometimes we underestimate the desire of the reading public to experience new ways of writing. In the heyday years of Eastgate, there was an audience and national coverage. Last year, there was a line for Electronic Literature & Its Emerging Forms at the Library of Congress. (curated by Dene Grigar and Kathi Inman Berens; host curator: Susan Garfinkel) This week in Electronic Literature: Theory and Contemporary Practice, I look forward to student traversals of Interactive Fiction and to beginning an exploration of hypertext literature. Sponsored by the Princeton Program in American Studies and by the Council of the Humanities, our course now meets in the splendid new DH center! I n the electronic literature community, we are not likely to sell over two million copies, as Infocom did. But that does not mean that the reading public is not interested in our work, nor that the increasingly blurred lines between narrative gaming and electronic literature are not healthy for our field -- providing, of course, that as individual artists our vision encompasses this.

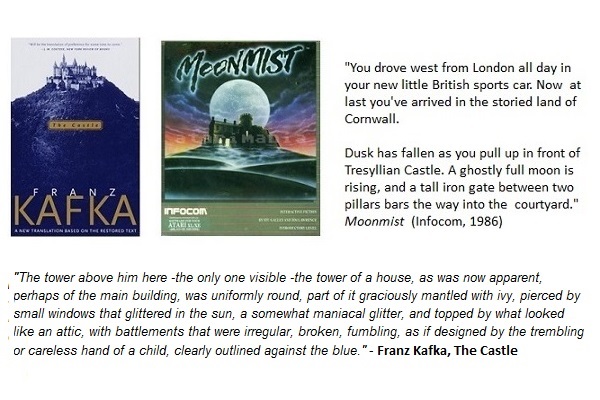

September 27, 2014 W hen, as is all too often necessary, one approaches early Interactive Fiction without the original maps and manuals, something is missing, or so I thought today as I unfolded the map of "Tresyllian Castle" from The Lost Treasures of Infocom collection. (Moonmist, Infocom, 1986.) I remembered writing Uncle Roger in 1986 for Art Com Electronic Network, the same year that Moonmist was written by Stu Galley and Jim Lawrence. Seeking ways to avoid the need to redo the documentation for the DOSBox emulator version of my own work, today, in The Lost Treasures of Infocom Manual, I was reading ghost stories associated with Moonmist. Several thoughts emerged from these recollections, readings, and procrastinations, as with pleasure I continued to read the documentation for The Lost Treasures of Infocom: 1. It was not because I did not like Interactive Fiction that I reached for a different authoring structure. Rather, I had a different vision. If you approach Uncle Roger without a knowledge of Renaissance scene-based comedy or of the reasons for using The WELL's PicoSpan conferencing system to emulate early between-acts comedies; if you don't know the ghost stories of the Cornish Coast (Moonmist) or the stories of the chip wars in Silicon Valley, (Uncle Roger) you may miss something. Documentation of new media works is important. 2. The different visions, with which some writers/programmers shifted the dialogue to hyperfiction, are important. In this way, art and literature travel, particularly in times of great cultural flux. Indeed, the connection of art with continuing technological progress, that is prevalent in new media, is not so different than what occurred during the Renaissance. Nevertheless, as continually happens in art history, we are beginning to revisit early works of electronic literature with pleasure. Classic works from the 1980's have acquired a patina. I look forward to next week's class on Interactive Fiction in Electronic Literature: Lineage, Theory, and Contemporary Practice. It would be of historic interest to see Interactive Fiction running on 1980's computers. But, from a writer's point of view -- as emulators of classic Interactive Fiction appear on my screen -- I don't see that much (other than the print documentation) is lost in the emulator versions. And I like the way Uncle Roger boots up on DOSBox. It is time to write better documentation T his week's addition of only three lexias has changed the view of 17th century Massachusetts in The Not Yet Named Jig. The process continues to surprise. I am haunted by the need for documentation. The colors of the trees are beginning to subtly change. It is a time for apple cider, cookies, and walking in the woods. The new digital humanities center at Princeton is dazzling. Ten papers have been received for Social Media Archeology and Poetics. (MIT Press, 2016) The practice of coffee house reading and editing of these papers has made what might have been a task, a pleasure.

September 20-21, 2014 O n Tuesday, September 16, Princeton students interested in studying, criticizing, and writing electronic literature, joined Malloy and Wulfman's seminar on Electronic Literature Lineage, Theory, and Contemporary Practice. We are only at the threshold of what can be created in electronic literature; it is an exciting time to be teaching and learning in this field. I look forward to class traversals, discussion, and creative projects in the coming weeks. W hat Virginia Woolf thought about Jonathan Swift's description of the Lagado Machine, I do not know. The Lagado Machine is not resonant of the elegant, writerly constraints that shape the structure of The Waves. Nevertheless, in September, in the first week of my discourse on the importance of authoring systems, it is time to reintroduce this 18th century authoring machine, which Swift describes in Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, Chapter V:

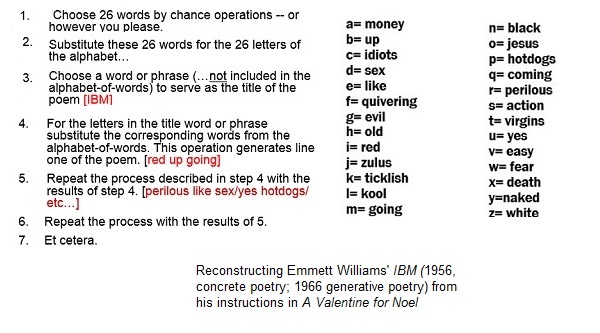

T ime travelling in the history of electronic literature, this week in the 10th Century in Medieval France, I encountered Wibold, the archdeacon of Noyon, who hacked dice to turn gambling (forbidden to clerics) into a dice-generated game of acquiring of virtues. "it is very appropriate that having abandoned vices according to the [canonical] rule, [clerics] cast lots for themselves in order to acquire virtues," he noted, according to Richard Pulskamp and Daniel Otero, Wibold's Ludus Regularis, a 10th Century Board Game, Loci, June, July 2014. (hosted on the website of the Mathematical Association of America) In this prequel to The Chaunce of the Dyse, the cleric possessing the most virtues was the winner. The authoring strategy, described in detail in Pulskamp and Otero's paper, included imprinting the dice with letters. T his week, I returned also to Fluxus poet Emmett Williams' A Valentine for Noel, spending some time to look at how he first -- without a computer in 1956 -- created the algorithm for a Fluxus poem. Ten years later, in 1966, when asked to create a computer poem, (probably by James Tenney) Williams used the same algorithm to create IBM. The image below, which illustrates the process, was made by combining Williams' instructions in A Valentine for Noel, the words he selected, and (in red) the beginning of the output.

"...what the poem amounts to if carried out too far, is an eternal project, and for most of us eternity is more time than we have at our disposal for perfecting works of art" - Emmett Williams

The woods in Princeton in late summer; the beginnings of new paths

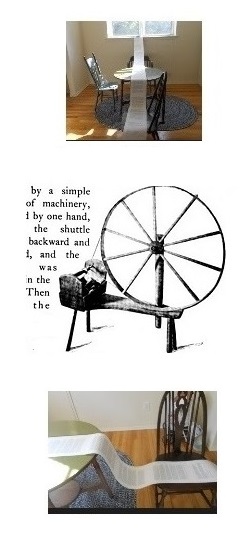

I have not worked in this way since the installations Cathy Marshall and I created for Forward Anywhere (for the Xerox PARC 25th Anniversary exhibition and for the ADA show at the Artemisia Gallery in Chicago) and the installation I created in conjunction with The Yellow Bowl for an exhibition that Joseph Delappe curated at the University of Nevada in Reno. But it is continuing practice -- sometimes, as Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop did at MLA2014 -- utilizing ephemera and printed materials to enhance screen-based work. The work of information art, I am conceptualizing will riff on two works (both begun in 1988) that used chance operations in different ways: its name was Penelope (published by Eastgate in 1993) and Free Values. (Documentation from Free Values was recently exhibited at di Rosa.) The texts in this new work will address the contingencies between the experimental exploration of materials and structure in creating artists books and the experimental exploration of authoring systems and content in electronic literature. 1. Electronic literature will be represented by a screen-based generative hypertext of nonfiction lexias, perhaps excerpted from Authoring Software. 2. An accompanying handmade or hand painted artists book-like container will present the viewer with the opportunity to choose at random from small scrolls tied up with ribbons -- such as those used to create Free Values. On these scrolls, words about the process of creating artists books will be written by makers of artists books. M oments of respite this week: an American Studies dinner for Representative Rush Holt, with good company and a memorable buffet at Prospect House; writing new lexias for The Not Yet Named Jig; a coffeehouse-situated exploration of Stacy Horn's wonderful account of how she founded EchoNYC; a series of short walks in the woods and along a beautiful brook.

September 12, 2014 T he light/dark landscape of late summer, so transcendent in a few short memorable walks beside streams and late summer flowering meadows; I sat one afternoon beside a magnificent corn field and did not write or read until I got home. Then, the experience seeped into the new lexias of The Not Yet Named Jig. "...what the poem amounts to if carried out too far, is an eternal project, and for most of us eternity is more time than we have at our disposal for perfecting works of art", Fluxus poet Emmett Williams writes to introduce A Valentine for Noel. (Stuttgart/London/Reykjavik: Edition Hansjorg Mayer n.d., n.p.) I am interested in how Williams "decided to temper the generative dimension of the poem with a cyclical dimension." (The poem, IBM, is circa 1966; the poet's authoring strategy is documented in A Valentine for Noel.) In this same week, there was the wonderful energy of the students returning to the Princeton campus and the anticipation of teaching electronic literature -- which has been so central to my life since I first envisioned in 1986 the extraordinary kinds of writing that are possible with words on the screen. I look forward to the work of our students; the work students did in my Social Media Poetics class last year is still -- with its variety and innovative approaches -- on my mind. I also look forward to team teacher Cliff Wulfman's interesting choices of precursors. Virginia Woolf's The Waves is not a usual choice, in this respect, but it is a perfect example of how the process of creating experimental print literature parallels the creation of electronic literature. Authoring Software opened September with Andrew Plotkin's Interactive Fiction tutorial, The Dreamhold. Maria Mencia's "birds" -- flying across the screen singing with human voices -- were an exhilarating classroom sound test. Early hyperfiction from Eastgate has arrived; there may even be an old IBM PC on which to run The Lost Treasures of InfoCom; I am interested in discovering how Carolyn Guertin and Katherine Jin are creating their bilingual interactive narrative app, Wandering Meimei. M eanwhile, papers are arriving for my MIT Press book on Social Media Archeology and Poetics, inspired by last year's Princeton American Studies class on Social Media History and Poetics. Social media is becoming an integral part of our culture; the lineage of social media is important. But existing documentation has been incomplete and/or in accessible. This book seeks to address these issues. It is a week where everything seems interesting, and there is much to look forward to!

September 7, 2014 T he number of lexias written into The Not Yet Named Jig now passes 50. For lexia 51, into the code, I wrote Puritan statute 23, which is core to the narrative. Then, I printed out the whole and taped together the pages. Starting at the window in my small dining nook, I stretched the resultant scroll across the table, over a chair and down to the floor. Afterwards, it was time to revisit issues in The Not Yet Named Jig, as it exists so far.

But I am not yet ready to divide the lexias into several files, nor am I sure that this is desirable. More lexias will need to be written before a decision is made on this issue. Relatedly, editing of the lexias written so far will not be done until the work is completed or nears completion. Seemingly minor content edits can disproportionately alter the greater meaning. O n a contingent class prep path, this week I returned to a continuing exploration of the medieval literary game The Chaunce of the Dyse. (The Chance of the Dice) Like random processes themselves, works such as The Chance of the Dice enter an artist's environment, submerging and emerging in unexpected ways -- for instance in 1988, with Free Values and 23 years later in March 2011 at an International Graduate Student Conference hosted by the UC Berkeley Program in Medieval Studies, where the conjunction of oral literature and reading in the Middle Ages was set forth in a series of panels on "Reading The Middle Ages" and of particular interest was Matthew Milo Sergi's talk on interactive readership in The Chance of the Dice. In my current understanding, The Chaunce of the Dyse ( MS Fairfax 16 and MS Bodley 638) consists of three introductory stanzas and 56 short narratives, keyed by combinations of the throw of dice. When the game was played, a master of ceremonies read the poetry that introduced this literary game. Each player rolled the dice three times to key the results to a text. The player then read aloud the text assigned to him or her. Based on then relatively contemporary works, such as Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, texts were personal, satirical, literary, character building, character destroying, embarrassing, pleasing. In Ethics and Eventfulness in Middle English Literature, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009) J. Allan Mitchell observes that "The Chaunce of the Dyse haphazardly throws up allusions, attempting by chance to close the gap between literature and life, past and present, 'game' and 'earnest'. This is the way the game produces, for a coterie of readers, the conditions of possibility for events to happen that confer unforeseen meanings on literary experience, respectively and prospectively." (pp. 63-64) It would be of interest to see what the entire manuscript of The Chaunce of the Dyse looks like, I observed, as starting at the window, I stretched the scroll of the code and lexias for The Not Yet Named Jig across the table, over a chair and down to the floor.

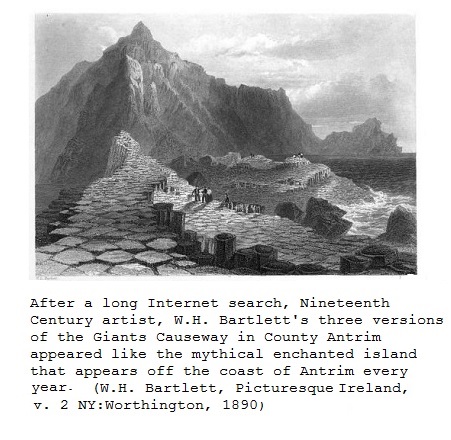

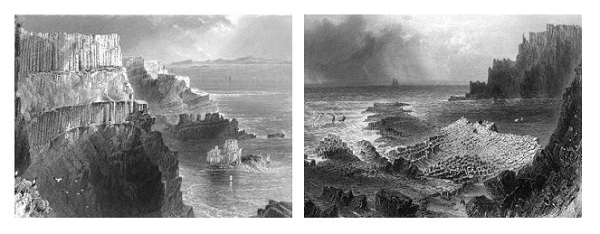

August 30, 2014 S ent by Wampanoag myths of the giant Moshup, who created the island of Nantucket by emptying the ashes of his huge pipe into the sea, this week I looked at parallel stories of the Irish giant Finn. How Finn created Lough Neagh when he tore a large piece of land from the ground and threw it at his rival in Scotland; how he missed and in so doing created the Isle of Man in the Northern Irish Sea; and the many conflicting accounts/imagined accounts of why Finn created the Giants Causeway. It was a passageway between Ireland and Scotland. It was a dock for a boat that became the Island of Staffa. It was a bridge to an epic battle between Finn and the Scottish Giant Benandonner. It was a path to Staffa, where lived a large woman with whom Finn fell in love. Mythologies encountered in many conflicting versions may be creatively explored in electronic literature genres that in various ways interface multiple paths through narrative information. In Interactive Fiction or in hyperfiction, parallel mythologies might exist as parallel world models, which the writer has systematically created; which the reader cannot discover without continual exploration. They might be set out as unbordered parallel columns on the screen, rhythmically playing with/against each other in a measured work of polyphonic literature. They might be written as separate lexias in a work of generative hyperfiction, where different versions submerge/emerge when the narrative is generated at the will of the computer, and their meaning is magically changed by the lexias that randomly frame them.

"The multiple readings of the text finally exist not so much in what the lexias say but rather in the relations they forge with one another. These relations come into existence and dissolve with each reading and unfold into different versions of the text" - Jaishree Odin, "Hypertext and the Female Imaginary ("Judy Malloy's its name was Penelope, p. 58-63) 1. "Benandonner being thus left without a pretext walked over and fought the Irishman, who not only won the battle but afterwards generously invited his rival to take an Irish wife and settle in the country. This kind bidding being accepted, the causeway was no longer needed, so it was sunk under the sea, except the ends on the opposite shores, which were left to prove the authenticity of the story." W.H. Bartlett, Picturesque Ireland, v. 2 NY:Worthington, 1890 2. In The Not Yet Named Jig, Walter Power tells the story above, but he also narrates the story in others ways, including a version in which Finn created the Giants Causeway when he fell in love with a large woman, who lived on Staffa, an island off the coast of Scotland. Finn crossed to Staffa on the causeway, and on Staffa, he made for his love a melodious cave: An Uamh Bhin. 3. The "enchanted island seen annually floating along the coast of Antrim" appears in Ann Plumtre, Narrative of A Residence in Ireland, The Summer of 1814, and That of 1815. London, 1817. p.124

August 22, 2014

The first was "A Feel for Prose, Interstitial Links and the Contours of Hypertext", a chapter in Michael Joyce's Of Two Minds, Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics, in which Joyce -- remembering Buffalo, or driving in the mountains, or meeting Mark Bernstein near Niagara Falls -- eloquently riffs on hypertext and hypertext literature: "We play ping to the pong of an unseen program" "We construct the electronic text by our choices, but we only come to know what we have written by understanding the choices of others." The second was "Some Artware for Macintosh Computers", MicroTimes, (May 31, 1993) where, while on a desert hill hike in Arizona -- walking up a dry, rocky path, bordered with yellow, blue, and pink flowers and dramatic multi-branching saguaro cacti -- I review recent hypertext literature and remix some words that Stuart Moulthrop wrote in After the Book: "'I've always thought polysequential was a better way to describe hypertext,'" he said." "'If you have as story to tell, isn't it best to tell in a straightforward manner?' a friend asked that evening. 'Every writer has his or her own ways of telling a story.' I say. 'Every artist has a different vision. It is not a question of replacing the sequential book...'" Michael concludes his paper with these words:

"We must listen so carefully to one another, how the stones splash.

August 14, 2014

M eanwhile, in The Not Yet Named Jig, I riffed on 17th century historian Geoffrey Keating's "Farewell to Ireland". Walter Power will never see Ireland again. The members of his family who were still alive at the time of The Transplantation in 1654 were exiled to Connaught. He has fallen in love with a Puritan woman. He does not expect to ever see his homeland again. Beside the Mystik River, in the early morning, Keating's words are echoing in his mind Viewing images on the Internet, at first I was surprised by how much the River Suir, that flows through Waterford and down to the harbor, looks like the Mystik River and then I realized that -- because Malden now longer looks the way it did 350 years ago, -- I had imagined 17th century Malden in the beautiful woods, fields, and rivers of 21st century Princeton.

August 9, 2014 W hen The Lost Treasures of Infocom arrive in the same week as a new Princeton TigerCard, a book contract for Social Media Archeology and Poetics, Kathi Inman Berens' excellent article about Uncle Roger in Literary and Linguistic Computing and a much needed pair of new walking shoes, it is either mid-summer Christmas or a good week to stand back and look at where the writing is heading. Perhaps this is what I should have done on Wednesday before I headed into a maze of fields and unmarked trails with new shoes and no "The Lost Treasures of Infocom Hint Book". The paper I had brought with me to read on this hike into a wildlands preserve was appropriate in a week that merged early social media with electronic literature. It was "Browsing the WWW by Interacting with a Textual Virtual Environment -- a Framework for Experimenting with Navigational Metaphors" by Andreas Dieberger in the venerable HYPERTEXT '96, Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Conference on Hypertext. Although written in the transitional era between the command line and GUI interfaces, (and thus would need to be retooled for contemporary systems) the idea set forth -- that if shared conversational MOO platforms were integrated with WWW systems, the resulting platform could provide a user environment where discussion between people searching for online information would allow the sharing of resources and ideas -- is worth revisiting. But what happened after a small picnic in this softly-lovely place of many trails and the reading of this entrancing paper was that (accustomed to walking in the woods) I lost my bearings in the maze of open farm fields and could not find the parking lot. The amount of crutches walking on new shoes needed to find my bearings (done by finally locating a familiar clump of trees in the distance) was unnerving. Once in a while, the trajectory of development of a writer's works of electronic literature, much like the trajectory of one's own life, needs to be surveyed from a distance. I had ordered The Lost Treasures of Infocom, not only because I wanted to show Princeton students the floppy disks, the maps, and the documentation that were a part of the experience of Interactive Fiction but also because it was a link to my path to electronic literature. N oting that among the IBM PC floppy disks I had received was Dave Lebling's The Lurking horror, I returned to my classic paper on Uncle Roger to read how I had explained the different direction I took in 1986.

_______________________ I read with interest my own words (submitted to Leonardo on May 5, 1989) in which I contrasted the experience of The Lurking Horror with that of Uncle Roger, noting that I might write this differently today, while at the same time finding it of interest that (coming from a place of alternative experimental fiction; coming from a desire to restore writer control of the narrative while at the same time effectively using computer mediation to provide a different experience than print) I was reacting against Interactive Fiction at a time when most people did not even know what it was. I wanted the protagonist to be a young woman experiencing male tech culture, so in Uncle Roger, the MIT culture in early IF is a Silicon Valley bedroom community. Reinforcing my sense that intrinsic to the wonder of the early Eastgate publications was the packaging and the print notes, The Lost Treasures of Infocom (1991) came packaged like an artists book with 10 IBM floppy disks, (IBM XT or AT) and a plethora of "feelies". Essentially, the print material here and in the early Eastgate titles were primary interfaces to text-based electronic literature. I have explored this issue several times recently, including in my interview in The Literary Platform.

...A good week to stand back and look where the writing is heading.

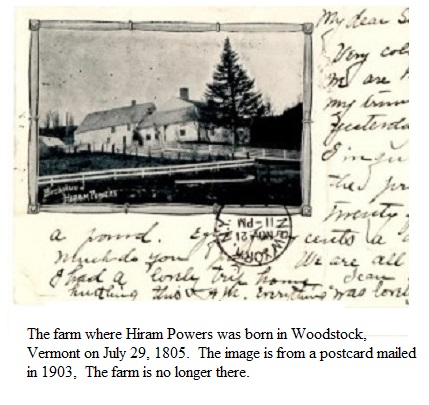

A t this time, I am not inclined to write the story of what actually happened between Walter and Trail that resulted in their conviction for pre-marital fornication, their marriage, and the exodus of not only Walter and Trial but also Ralph and Thank Lord Shepard and their children to the Concord area. This narrative would have to be fictionalized; that is territory on which I do not want to tread. Instead, From Ireland with Letters will finish with a coda in which Máire Powers and Liam O'Brien journey to Woodstock to see the site of the birthplace of Trial and Walter's descendent, the 19th century sculptor Hiram Powers. What happens between Máire and Liam, in a country inn, will metaphorically conclude From Ireland With Letters.

August 3, 2014

"The objects in the cabinet are as varied as memories in a dream." Andrew Plotkin, The Dreamhold W hile writing lexias to The Not Yet Named Jig, I continue to consider how the world models, that are a foundation of Interactive Fiction, are also created in generative hyperfiction -- focusing this week on narrative detail. If these forms seem very different, it should be remembered that neither I nor the creators of Interactive Fiction know precisely what the reader will see or encounter in traversing our finished work. A reader might also observe the similar experience of arriving in the same place over and over again. In IF, the reader might eventually resort to mapmaking, help files and restarting to reveal the story. In generative hyperfiction, the time dependent nature of some pseudo-random generators may mean that at certain times certain lexias occur more frequently. Over a period of time, the narrative will emerge. In both cases, the reader's experience is enhanced with a richness of detail, and -- whether the work is displayed on the screen at the will of the computer or displayed on the screen in response to the reader's instructions -- the nature of details that we set forth in building a world model is a cogent consideration. For instance, the experience of Emily Short's Bronze includes not only maze, puzzle, riddle, quest but also an erotic aura of narrative tension that is built with dramatic details -- such as the remembered conversations between The Beast and the protagonist that occur in various rooms. Conversely, disconcerting, clanging, or mirthful, incidental details, such as the stool or stilts necessary to dance with The Beast, contrast with the immersive tension of the quest. C ontingently, in The Not Yet Named Jig, from a 1658 text, concerning the behavior of Priscilla Upham's suitor Paul Wilson, (whom her father had forbidden from his daughter's company due to Wilson's prior convictions for disorderly conduct and his drunkenness) many disconcerting, clanging details were composed this week and threaded into the whole -- contributing both to an understanding of the issues of the Colonial world model and to the slow building of the narrative. The text I used/am using as a foundation for this and next week's lexias is as follows:

"Upon the last day of April [1658.] in the night at too of the cloke after midnight ; There was a noise heard by Phinehas Vpham and his Wife At the side of the house ; by which they ware awakned out of their sleepe his wife being awakned first was strucke with agreat feare : Wee heard musicke and dansing which was no smal disturbance to us : And they came harkeing unto our window where wee lay ; which they did three times ; between which times they danced and played with their musicke : with much laughter." In generative hypertext or in Interactive Fiction, such texts, whether quoted by or written by the author, serve also to offer the reader a consideration of the medium itself. For instance, the experience of the Interactive Fiction Zork includes not only maze, puzzle, riddle and quest -- in a work that on the surface concerns mainly the dangers involved in the acquisition and storage of 19 objects -- but also reflective details that submerge and emerge along the way, such as the wind-up canary: "The canary chirps, slightly off-key, an aria from a forgotten opera. From out of the greenery flies a lovely songbird. It perches on a limb just over your head and opens its beak to sing. As it does so a beautiful brass bauble drops from its mouth, bounces off the top of your head, and lands glimmering in the grass. As the canary winds down, the songbird flies away." E lectronic literature is not only created in different ways, it is also read in different ways. From a pedagogical point of view, allowing students to develop their own authorial or critical vision -- while at the same time introducing different possibilities for fulfilling that vision -- is important.

July 26, 2014

T he arrival at the long sought swinging bridge was not anticlimactic. In the middle of the woods, the staircase to the bridge appeared suddenly. With forbidding elegance, the bridge itself stretched across the wide brook. In places the brook is clear, and you can see the bottom; in other places it flows dark and muddy. For those who are familiar with these woods, I note that in other weeks, the maze of trails described in these pages was not encountered at the main entry. But on Friday, I took the direct route and arrived at the swinging bridge without much difficulty. The bridge itself was another matter. This time, instead of Nick's Montfort's Twisty Little Passages, I had brought Jaishree Odin's Hypertext and the Female Imaginary and was not afraid to walk the bridge on crutches. But what if, as will happen occasionally, I dropped one of my crutches, and it fell off the bridge into the water. How then would I return home? "The narrative strategy used in the hypertextual environment lies in navigating through a body of lexias or textual segments that allows the tracing of varied paths in the midst of open possibilities. Hypertextual tracing does not aim at reaching a destination; rather, the act of tracing itself becomes the object of navigation, so that the discrete nodes are subordinated to the lines of traversal" - Jaishree Odin (.p. 31) Wisely I retraced my steps and found a secluded place near where the trail forked. Setting out a small picnic of coffee cake and coffee, I began with pleasure to read Hypertext and the Female Imaginary: (p. 33) "Postmodern and postcolonial art does not locate the centered sujectivity of the artist but expresses his or her textual embodiment in a possible historical moment, always acknowledgibg that any artistic representation is just that -- a represntation, not a complete total picture of reality. Fragmentation and discontinuity, then, comprise tools that these artists use to allow for polyphonic narrative structures." W riters sometimes distort known places layering them onto localities where they have never been, camouflaging places that they not wish the reader to recognize, or conveying, in a writer's search for his or her vision of representation, a veiled recognition of ancient place.

The long sloping hill, West of the Mystik lakes, on which the woman who was the Sachem of the Massachusetts tribe walks down to the lake (in the other lexia that I wrote this week) is probably the place where I learned to ski as a child, or so I discovered as I cycled through local histories and geographies until I was able to locate the likely place of the summer residence of the Sachem and her tribe.

In the hills West of the Mystik lakes, The morning depicted in the "Dawn" section of The Not Yet Named Jig is 1660. The Sachem's death has been given variously as 1650, 1662, and 1667. Whether it is she herself or her spirit who walks down this hill is immaterial. I do not want to write exactly where this hill is, nor did I at the time know that we were skiing on what was once the land of a woman who was a legendary woman chief, whose powerful presence in the difficult time of 17th century Massachusetts has long been trivialized or obliterated in history books. In the winters of my childhood, there was seldom anyone else packing trails below her home. It was not a ski area, just a gentle slope reminiscent of a hillside preserve in Princeton where I walked last Sunday. In Princeton last Sunday, there was a profusion of beautiful wildflowers of bygone days, row after row of pink and yellow wildflowers with splashes of orange and white Queen Anne's lace. Near the trail there was milkweed, as if waiting for the children to gather milkweed silkdown for candle wicks -- in the fields near the river in the autumn, just before the first frost. In this summer of early electronic literature and social media poetics, earlier in the week I explored Kafka's The Castle in a Princeton ice cream parlor, where even the incongruous setting did not dispel the feeling of ominous despair which The Castle engenders. Surely, sitting in an ice cream parlor reading Kafka, the reader of interactive fiction will recognize the distorted environment, the inexplicable encounters, the vague sense of danger the feeling that a metaphoric quest will not be fulfilled, the experience of returning many times to the same place. Cannot enter. Cannot find a way out. Yet if some read IF for the riddles, I read for the details and the language and in the process am often rewarded with the pleasure of eliciting the treasure of the storyteller's words.

July 20, 2014

I n the midst of writing lexias into the fiddlers_dawn code that produces The Not Yet Named Jig, as is usually the case, the point has been reached that the writing of the work itself has become more important than the documentation in this notebook. But documentation is important in electronic literature because there are not always models for the paths we are taking. Not only does documenting the creation of electronic literature clarify the process for ourselves, but also our notes may be helpful to others who work with electronic literature. Additionally, a writer's notebook is a source of research documentation and bibliographic information. For instance, I should at this point record the sources for the story -- inserted into The Not Yet Named Jig in this week's lexias -- of how in Malden in 1651 Marmaduke Matthews preached a sermon on the text of Zechariah 3:9 and what happened when he was subsequently summoned to the Massachusetts General Court on the charge of preaching heretical doctrines. One of the most interesting facets of the Marmaduke Matthews case is a 17th century letter to the General Court in defense of Mr. Matthews. It is signed by 36 women of Malden, including ThankLord Shepard.

The main sources are "Marmaduke Matthews" in

Deloraine Pendre Corey, The history of Malden, Massachusetts, 1633-1785. Malden, 1899. pp 126-164 Due to interpretation difficulties when certain randomly selected lexias followed "remove the iniquity of that land in one day", I used Zechariah 3:10 and part of Zechariah 4:1 in The Not Yet Named Jig:

"For behold the stone that I have laid before Joshua; upon one stone shall be seven eyes: behold, I will engrave the graving thereof, saith the Lord of hosts, and I will remove the iniquity of that land in one day. And the angel that talked with me came again, and waked me, as a man that is wakened out of his sleep. And said unto me, What seest thou?" R eturning to interactive fiction, this week hosted a metaphoric circular voyage from the trails of the Institute woods to The Not Yet Named Jig to the "white house" in Zork, where, having entered the house and progressed past the kitchen, I entered the living room:

"You are in the living room. There is a door to the east. To the west is a wooden door with strange gothic lettering, which appears to be nailed shut. > read lettering The engravings translate to, "This space intentionally left blank"." In the kitchen, I "took" a glass bottle and possibly a clove of garlic. In the living room, I took the "battery-powered brass lantern" and the "elvish sword of great antiquity". In this episode, I also ate lunch, ascended the stairs, and frightened The Grue with the battery powered lantern.

In part because of the details of MIT culture, (for instance, technical reports often contain flyleaves with the "This space intentionally left blank" message) so far, I have found Zork much more interesting than expected. I'm not unfamiliar with this culture, but would also credit Nick's close reading for pointers to the cultural importance of the detail in Zork. I t is time to work on my book on Social Media Archeology and Poetics.

July 12, 2014 O n a trail that theoretically led to a brook, a hypertextual walk through the woods led on Thursday to a place so like the place I had been on Saturday that at first I thought that I had arrived at Saturday's meadow. But on Thursday, the clover was pink, and there was only one trail across the field. I sat down for a small breakfast picnic and considered how generative hypertext is built with the gradual accumulation of details. If at times writers of electronic literature purposefully avoid expected fictional conventions and strive instead to create an experience that fulfills a different vision, this does not mean that the revelation of character or the development of narrative tension are not possible, if we so desire. Generative hypertext, for instance, allows a slow cumulative buildup of narrative detail/repeated narrative detail. At home seven new lexias were written that centered around/diverged from a birth locket that mysteriously appeared in the hem of the only shirt Walter Power owned when he arrived in America. These lexias were written into the fiddlers_dawn program that produces The Not Yet Named Jig. Then, over and over I "played" the work until details that should emerge in the next series of lexias were suggested.

"...there is the exploration of evolving human relationships T his week, the studious process of revisiting of historic electronic literature continued with Dick Higgins' description of his creation of Hank and Mary, A Love Story, A Chorale. Remarkable for the complex polyphonic ballad it produces with the permutations of only four words: "HANK SHOT MARY DEAD", Hank and Mary moves darkly down continuous feed computer paper -- with repeated columns of the chorus/continuo "HANK SHOT MARY DEAD" playing against permutations such as -- "MARY SHOT HANK DEAD"; "HANK MARY DEAD DEAD", and finally "DEAD DEAD DEAD DEAD". Written by Dick Higgins and programmed in FORTRAN IV by Higgins and James Tenney, Hank and Mary is documented in Higgins' chapbook Computers for the Arts. (Abyss Publications, 1970) Note that the otherwise interesting book, Mainframe Experimentalism, truncates Higgins' chapbook. Read the whole, currently available at http://bin.sc/Readings/New%20Media/Higgins_Dick_Computers_for_the_Arts.pdf. F riday's coffeehouse rereading was Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities. Trapped in a flow of metaphor and words, fantasies of Far Eastern cities metamorphosize from the city of Venice; arguably Venice becomes a myriad desirable women; and in the process, devices of electronic literature are foretold, as -- in this precursor to Calvino's next work, The Castle of Crossed Destinies -- language barriers are overcome with gestures, actions, sounds, and the unusual objects, which Marco Polo takes from his knapsack in the court of Kublai Khan. A man tells stories to another man. And along the way, the reader, male or female, is seduced by Italo Calvino's vision of writing, storytelling, and desire. In a Princeton cafe, sitting down with apple strudel, crème fraîche, and coffee, I opened the paperback copy of Invisible Cities (which I had carelessly stuffed into my pocketbook) and discovered (on the front and back flyleaves) my own notes from 1996 when - entranced by Calvino's vision -- I quoted from Invisible Cities at intervals in The Roar of Destiny: